les Nouvelles July 2023 Article of the Month:

Trade Secret Economics And Value

Managing Member

Kraft Analytics, LLC

Nashville, TN

Like other forms of intellectual property (IP), trade secret value may arise from two primary sources. The first is proprietary competitive advantage gained through use of the IP coupled with the right to exclude others from such use. The second is by monetizing IP directly through licensing to others. While stand-alone trade secret licensing may not be as common as with other forms of IP, it does occur.1 Governments provide patent holders the right to exclude others using a patented invention for a limited time based in part on invention disclosure. In contrast, the right to exclude others from use of a trade secret arises from limited disclosure and reasonable efforts to maintain secrecy.

This article explores economic factors relevant to trade secret value. For purposes herein, I use the trade secret definition contained in the U.S. Economic Espionage Act of 1996 (EEA) which defines a trade secret as:

all forms and types of financial, business, scientific, technical, economic, or engineering information, including patterns, plans, compilations, program devices, formulas, designs, prototypes, methods, techniques, processes, procedures, programs, or codes, whether tangible or intangible, and whether or how stored, compiled, or memorialized physically, electronically, graphically, photographically, or in writing if the owner thereof has taken reasonable measures to keep such information secret; and the information derives independent economic value, actual or potential, from not being generally known to, and not being readily ascertainable through proper means by, the public.2

Through the Defend Trade Secrets Act of 2016 (DTSA), the EEA was amended to provide a private right of action for trade secret misappropriation in cases involving interstate and/or foreign commerce. The DTSA was modeled after the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA), which has been adopted by 48 states.3

In Search of Proprietary Competitive Advantage

Human beings respond to incentives. This fundamental tenet of economics is demonstrated every day with business owners who work to maximize profits by selling more, selling faster, selling at a higher price, and working to reduce costs. These efforts do not occur in economic isolation. Other than governments and monopolies such as utility companies, most enterprises compete for customers and revenues. Certain sources of advantage in business—including advantages and value arising from trade secrets—can be assessed based on relative economic importance and proprietary protection.

If two competing businesses maintain the same advantage— whether in the form of a production method, internally-developed software, marketing information or some other capability—then no advantage actually exists. However, an advantage exists with respect to other competitors that lack this source of advantage.

Economics literature is filled with references to advantage being viewed on a comparative basis. Adam Smith makes an early reference to this idea in The Wealth of Nations (published 1776) while David Ricardo uses the term “comparative advantage” in On Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (published 1817). Ricardo’s reference occurs in comparing the relative advantages of England and Portugal in producing cloth and wine at the time.

Critical factors in assessing value for a source of proprietary competitive advantage include its economic utility, the materiality of the benefit, and barriers that exist to prevent competitors from replicating the advantage. Economic utility speaks to the usefulness of the advantage, while materiality relates to its significance or weight. A source of advantage that is not very useful and not very significant holds little promise for being valuable. However, a source of advantage that is both highly useful and material holds the potential for meaningful value.

If a proprietary competitive advantage is to provide enduring value, barriers must exist to prevent others from legally identifying and replicating it. After all, if the source of an advantage can be legally identified after a quick Google search and then legally used afterwards, the advantage, if any, is short-lived and not valuable because it cannot be protected.

Intellectual Property Economics and the Free Rider Problem

Unlike tangible goods that are governed by laws of scarcity, information can be inexpensively shared and replicated. This creates unique economic circumstances for intellectual property and other information-based assets. Protections afforded by patent, copyright, trademark, and trade secret laws provide incentives for developers of IP to make initial and ongoing investments. Absent such protections, investments in IP would decline—and in some cases, not occur at all—due to the risk of others free-riding on the past work and investments of others. Speaking to this issue, Judge Richard Posner stated:

Intellectual property is characterized by heavy fixed costs relative to marginal costs. It is expensive to create but once created the cost of making additional copies is low, dramatically so in the case of software, where it is only a slight overstatement to speak of marginal cost as zero. Without legal protection, the creator of intellectual property may be unable to recoup his investment, because competitors can free ride on it; and so legal protection can expand, rather than as the usual case with monopoly contract, output. (“Antitrust in the New Economy,” Address by Judge Richard Posner, Date: September 14, 2000.)

According to Black’s Law Dictionary, a free rider is “one who obtains an economic benefit at another’s expense without contributing to it” or without “paying a fair price” for the economic benefit obtained. Due to free rider risks, the ability of an IP originator to obtain and enforce rights to exclude others from unauthorized or improper use is necessary for meaningful investments in IP to occur.

As indicated by Judge Posner, the difference between the high up-front costs needed to develop IP and relatively low costs generally associated with replicating and using IP encourages free riding. After all, free riders stand to gain the benefit of IP use without the risk of up-front investments. As a result, IP protection is needed to encourage investments in developing IP that provides societal benefit that might not otherwise occur without such protections. In the case of trade secrets, these protections are granted based on reasonable efforts to maintain secrecy and the information having value due to its secrecy.

Key Elements of Trade Secrets

Like other forms of IP, trade secret economics are shaped by the way IP protection enables proprietary benefits. Deconstructing the EEA trade secret definition cited earlier, three major components are revealed:

- Types of information covered, along with the various forms and methods of storage used to maintain this information, are indicated in the first paragraph of the definition.

- Reasonable secrecy measures must be taken by the owner to maintain trade secret protection as noted in the second paragraph of the definition.

- Independent economic value is derived from the information not being generally known and not being readily ascertainable through proper means as indicated in the third paragraph of the definition.

Expanding on these three major elements, the DTSA provides the following definitions:4

- “Misappropriation: (A) acquisition of a trade secret of another by a person who knows or has reason to know that the trade secret was acquired by improper means; or (B) disclosure or use of a trade secret of another without express or implied consent by a person who—(i) used improper means to acquire knowledge of the trade secret; (ii) at the time of disclosure or use, knew or had reason to know that the knowledge of the trade secret was—(I) derived from or through a person who used improper means to acquire the trade secret …

- Improper Means: (B) does not include reverse engineering, independent derivation, or any other lawful means of acquisition …

The issue of what constitutes improper means versus proper or lawful means of acquisition is a critical component in assessing trade secret value. The higher the barriers are to proper means of acquiring the information by competitors, the greater its proprietary value.

Trade Secret Categories

Three broad categories of trade secrets become apparent when considering the types of information cited in the first paragraph of the trade secret definition. It can be helpful to consider trade secrets in categories such as those noted below due to differing economic

characteristics.5

Software

Software can be protected by patent, copyright, and trade secret laws. If attempting to protect software as a trade secret, reasonable efforts to keep such information secret must be used to protect the source code and perhaps other elements of the system. This category of trade secrets includes methods, techniques, processes, procedures, programs, or codes.6

One reason software developers choose trade secret protection is to avoid public disclosures that might tip off competitors as to proprietary methods. Armed with this information, a competitor might legally design around the proprietary method thus hastening the demise of any advantage it may have provided. Another reason is compressed technology life cycles. Spending time and money protecting rapidly evolving software that could be rendered obsolete with an upcoming version may not make sense.

Technical Information

Technical information can involve scientific, technical, engineering information, patterns, program devices, formulas, designs, and prototypes, that may include patentable subject matter.7 But again, owners may choose trade secret protection to avoid disclosure and obsolescence risks such as those described above for software.

Business Information

Financial, business, and economic information can be classified broadly as business information. Generally, the business information a company might deem to be a trade secret involves information about customers, pricing, products, and suppliers.

Key Dimensions of Trade Secret Value

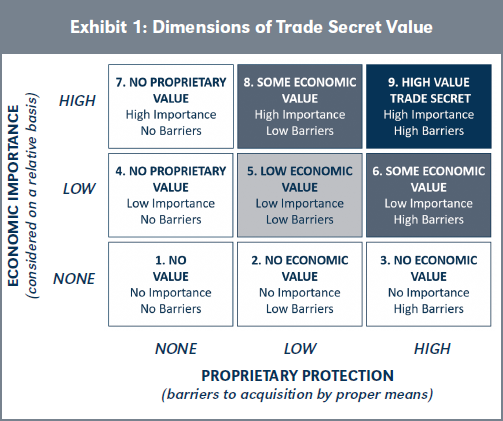

Exhibit 1 combines the concepts of economic importance and proprietary protection discussed previously as key dimensions of trade secret value and the assessment of independent economic value. Economic importance should be considered relative to other factors that contribute to value while proprietary protection considers barriers to others acquiring the information through proper means.

Imagine a production process that previously cost two dollars per unit to perform which now costs only one dollar due to a new trade secret.

If each product produced using this trade secret costs a total of one million dollars to make and 100 units are sold each year, the annual savings of $100 is immaterial. The trade secret has low economic importance in this setting.

Now imagine a product produced using the same trade secret that previously cost $10 to make, and one million units are sold each year. If sales remain constant, and the product now costs nine dollars to make, annual savings of one million dollars per year are realized. The trade secret has high economic importance in this setting.

Exhibit 1 illustrates the relationship between economic importance, considered on a relative basis as described above, and proprietary protection (i.e., barriers to acquisition by proper means).

The enumerated sectors identified in Exhibit 1 are discussed below:8

- Information that has neither any economic importance nor barriers to legal acquisition by others has no economic value. A good example here is information that might be deemed trivial. For instance, someone might know something interesting about the history of a company that others do not know. But if that information is not economically useful and could be readily found by others, if they chose to look, it has no economic value.

- Information that has no economic importance but low barriers to legal acquisition by others. This information has no economic value, even though some measures may exist to protect it.

- Information with no economic importance that is difficult to obtain legally still has no economic value. Imagine the CEO of a company who has decided to surprise his employees by painting the break room yellow. He comes in on the weekend, when nobody is there, and paints it himself. On Monday morning, employees see the yellow break room after the CEO worked effectively to keep this information a secret for an extended period of time. While this information would have been difficult for others to know given the high level of secrecy, this information is not economically important and thus has no economic value.

- Information that has low economic importance and no barriers to acquisition by proper means. Despite having some use, there is no proprietary protection, so this information has no economic value.

- Information that has low economic importance and low barriers to acquisition by proper means. This information has low economic value and may or may not be deemed a trade secret.

- Information that has low economic importance and high barriers to acquisition by proper means. This information has some economic value and may or may not be deemed a trade secret.

- Information that has high importance and no barriers to acquisition by proper means has no economic value. Despite being useful, this information has no proprietary value and thus no economic value. Consider the example cited previously of information that can be legally obtained from a quick Google search and legally used afterwards. While this information might be useful, it has no economic value because no barriers exist to prevent others from legally identifying and using it at no cost.

- Information that has high economic importance and low barriers to acquisition by proper means. This information is useful and more difficult for others to obtain by proper means and may or may not be deemed a trade secret.

- Information that has high economic importance and high barriers to acquisition by proper means. This type of information exemplifies a trade secret with “independent economic value” assuming such value is derived from “not being generally known to, and not being readily ascertainable through proper means by, the public.” The classic example of this type of information is the formula for Coke which is supposedly maintained under lock and key with very few people having access.

Trade Secret Valuation

Above, I consider factors relevant to the assessment of trade secret value and its independent economic value, a necessary element in establishing the existence of a trade secret.

In this section, I consider information and methods used to calculate the economic value for a trade secret or similar information that may not be deemed a trade secret.9

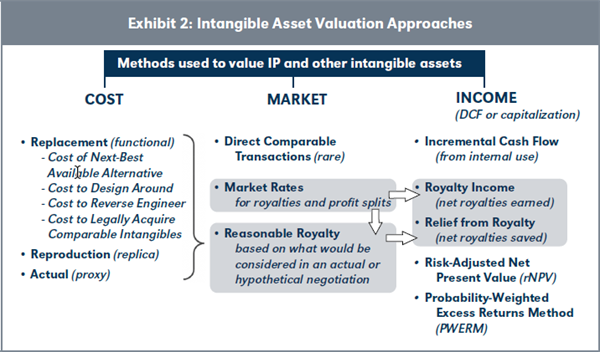

Exhibit 2, on page 41, summarizes types of information, types of valuation methods, and relationships between them. This exhibit illustrates how information from one area may be used as a valuation input in another area.

For instance, Exhibit 2 illustrates how cost-based information can be used in the determination of a reasonable royalty, which may also consider market-based royalty rates, which may then be used in an income-based calculation.

Cost-Based Approaches

Cost-based approaches are based upon the economic concepts of substitution and price equilibrium.10 A rational intangible asset buyer would not be willing to pay more than the cost to develop or acquire a comparable substitute. To the extent that multiple substitutes exist in the market, competitive forces tend to create an equilibrium price. In this setting, the prospective buyer would weigh options to make, buy, find, compile, or license the intangible. For example, with software the cost associated with building a functionally equivalent system (the “make” option) may be a relevant alternative to buying or licensing from others. Under the cost-based approach, the cost to obtain a comparable intangible asset is assessed. Three general measures of cost-based value are:11

Replacement Cost—the cost to obtain an intangible asset with comparable utility as of the relevant valuation date. Put another way, replacement cost considers the cost of a functionally comparable intangible. Some specific replacement cost considerations include: - Cost of the next best available alternative - Cost to design around - Cost to reverse engineer - Cost to legally acquire comparable intangibles

Reproduction Cost—the cost to develop a replica of the original intangible as of the relevant valuation date. While replacement cost considers a functional replacement, reproduction cost considers a replica in form and function.

Original Cost—the cost to acquire the original intangible. This cost, if available, reflects the original investment. It can be a useful measure of value on its own. It can also be a helpful proxy for other cost-based measures of value. However, the original cost’s usefulness as a proxy can diminish over time. If the valuation date is significantly later than the period of original creation, new techniques, approaches, and sources of information may have come into existence since initial creation that cause the replacement cost to be lower than the original cost.

A common use of cost-based valuation analysis occurs in patent infringement cases when, in assessing a reasonable royalty, consideration is given to non-infringing alternatives available at the time of the alleged infringement. Citing Grain Processing,12 the defendant in a patent infringement case may argue that, in an armslength negotiation prior to the alleged infringement, it would not have agreed to a royalty that costs more than an available non-infringing substitute. This cost-based value for an acceptable substitute may consider market- based information.

The idea of permissible alternatives is similarly relevant in a trade secret context. After all, the prospective user of someone else’s trade secret would not be willing to pay more than it would cost them to obtain it independently using proper means.

Market-Based Approaches

Market-based approaches are based upon the economic concepts of competition, equilibrium, and substitution.13 The most apparent application of the market approach relies on the use of prior arms-length transactions involving comparable intangibles. Unfortunately, several factors make the use of direct comparable transactions difficult, and rare in this setting.

First, intangible assets are often unique, and their value is contextual thus making direct comparability challenging.

Second, unlike stock market pricing, relevant intangible asset transactional data can be difficult to find.

Finally, intangible asset value is often provided through products, services, and processes that embody the intangible, thus causing its value to be intertwined with other sources of value. To value an intangible asset in this setting, its value must be isolated. This need to isolate intangible asset value is also apparent in litigation where calculations of IP damages often involve some type of apportionment exercise to strip away sources of value unrelated to the IP in question.

Due to challenges associated with direct application of a market approach for intangible asset valuations, typical application occurs indirectly, through royalty rates or profit splits that isolate IP value.

Exhibit 2 considers “Market Rates” and rates derived by assessing what a “Reasonable Royalty” might be.

“Market Rates” may consider: (i) established rates for the intangible being valued, if they exist; (ii) industry rates, and (iii) market rates for comparable intangibles.

A “Reasonable Royalty” considers rates or amounts that would result from a hypothetical or actual negotiation between parties given certain economic considerations. One such consideration is the cost associated with obtaining comparable intangibles through proper means as noted in the prior section.

Profit splits can be converted to a running royalty rate by multiplying the percentage split times the profit margin. For example, a 25 percent to 33 percent profit split in the context of a product line generating a 30 percent profit margin yields implied royalty rates of 7.5 percent and 10.0 percent of sales, respectively. Royalty rates derived from profit-split analyses may be used in conjunction with market royalty rates and other evidence in the determination of a reasonable royalty rate.14

Beyond royalty and profit split data, other market- based valuation metrics may also be available in certain situations. For instance, with computer software, metrics for programmer productivity (e.g., lines of code per month) can be used in conjunction with market-based programmer pricing to develop a market- based replacement cost.

Income-Based Approaches

Income-based approaches are based upon the economic principle of expectation.15 Under this approach, the value of an intangible asset is the present value of expected economic benefits arising from ownership or use of the intangible. As noted in Exhibit 2, discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis and capitalization of cash flows are the core income-approach methods.

Income-based valuation analysis should reflect future incremental cash flows (i.e., the benefit stream) attributable to the trade secret. These future cash flows may result from licensing income, or additional profits generated from trade secret use.

Use of the income-based approach involves determining: (i) the expected future benefit stream; (ii) the remaining useful life of the trade secret; and (iii) an appropriate discount or capitalization rate.

An expected benefit stream may be based upon historic activity that is expected to continue or specific projections of future activity. In either case, income-based analysis is forward-looking. The future profitability of the business, product, service, or process attributable to trade secret use—or some portion thereof—provides an appropriate basis for the benefit stream under the income approach.16

The duration of the benefit stream should reflect a reasonable estimate for the remaining useful life (RUL) of the intangible asset. The RUL for a trade secret could be based upon: (i) expected obsolescence; (ii) the time associated with competitors identifying the trade secret through proper means; or (iii) the time associated with competitors developing comparable approaches that provide a similar advantage. In a DCF analysis, the RUL dictates the number of future discounting periods.

Based on a finite RUL, cash flows would be discounted to a present value based upon projections for a finite period. However, a capitalization can be used to derive a value for an intangible asset with an indefinite life, as may be the case with some trade secrets and trademarks, neither of which have a prescribed statutory life.

Discount rates and capitalization rates are related. A capitalization rate equals the discount rate minus the expected growth rate of the cash flow.17 A discount rate should reflect a reasonably expected rate of return in the market for the investment based upon its risk relative to other investments available during that period of time.18 This rate should not reflect the return expectations of a particular investor, but rather a market return rate for a comparable investment.19

In cases where the benefit stream is based on royalty income or savings, there are two commonly used methods.

The royalty income method assumes the IP has been, or will be, licensed and that royalty income forms the basis of the benefit stream.

In contrast, the relief from royalty method assumes the IP is embodied in a product, service, or process and that economic benefit is derived from internal use. The economic benefit stream with the relief from royalty approach is the licensing expense avoided, which provides the owner with a “relief from royalty.”

In certain situations, it may be helpful to consider risk and uncertainty in different ways, using an income- based approach.

For instance, the Risk-Adjusted Net Present Value (rNPV) method incorporates the likelihood of success for a stage-gated process in the cash flow model. This approach is used regularly when valuing life science patents where clinical trial approval is required from regulators before market entry.

Another way to consider risk and uncertainty is through the development of alternative performance scenarios. This can be particularly applicable with IP embodied in new products for which there is no track record from which to develop reliable forecasts.

If it is helpful or necessary to develop a single value when using multiple scenarios, the Probability-Weighted Expected Return Method (PWERM) can be used. Under this approach, the likelihood of achievement for each scenario is assigned a probability weight so that a single amount can be presented.

Scenario analysis can be taken to the next level through Monte Carlo simulation in which many different scenario iterations are developed, based on stated input variable ranges using specialized software. The result is a value distribution range.

Conclusion

With a patent, copyright or trademark, the existence of the IP is unrelated to its economic value. But with trade secrets, the issue of value is relevant to both the economic merit and existence of the IP. Indeed, independent economic value stemming from secrecy is a trade secret requirement according to the definition cited herein. The approaches identified in this paper should be helpful in assessing trade secret economics and establishing trade secret value. ■

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): https://ssrn.com/abstract=4337753.

- This article uses narrative and concepts introduced in two previous articles by the author: (1) “Understanding the Economic Value of Trade Secrets” (ABA Section of Litigation for Intellectual Property, March 28, 2014), and (2) “Intangible Asset Valuation: A Comprehensive Framework,” (les Nouvelles, December 2020).

- 18 U.S.C. § 1839. This paper focuses on economic issues based on U.S. law as expressed in the EEA and DTSA. I understand legal and economic factors may vary in other jurisdictions.

- https://ogletree.com/insights/five-questions-you-shouldask-about-the-defend-trade-secrets-act/.

- See full text of DTSA for complete definitions for these terms and others. These definition excerpts are truncated to focus on key economic issues relevant to this article.

- These broad categories are cited for illustration purposes. Based on specific facts and circumstances, other categories may be deemed applicable in other situations.

- While the types of trade secret information cited here are particularly applicable to software, they may also apply to the other categories cited since programs may involve technical and/or business information and since methods, techniques, processes, procedures, and codes may apply broadly to technical and business information.

- This could include both utility and design patents.

- It is noted that certain categories of information “may or may not be deemed a trade secret.” This recognizes that trade secret determination may ultimately occur in a judicial setting. Factors noted herein are economic considerations relevant to this assessment.

- Certain information considered in this section was presented previously in “Intangible Asset Valuation: A Comprehensive Framework” as published in les Nouvelles, December 2020. Exhibit 2 is a modified version of Exhibit 1 from this previous publication.

- Robert F. Reilly & Robert P. Schweihs, Valuing Intangible Assets, 96-97 (1999).

- Gordon V. Smith & Russell L. Parr, Valuation of Intellectual Property and Intangible Assets, 160, 161 (2000).

- Grain Processing Corp. v. American Maize-Products, 979 F.Supp. 1233 (N.D. In. 1997).

- Reilly & Schweihs supra 96, 97.

- I cite a “25% to 33% profit split” here for illustrative purposes. While this type of split may still be relevant in certain settings, use of the so-called “25% Rule” in patent infringement litigation is no longer allowed.

- Reilly & Schweihs supra 113.

- While incremental profits and incremental cash flow may be different amounts, they are often comparable and are used here synonymously for the sake of brevity.

- James R. Hitchner, Financial Valuation: Applications and Models, 127 (2006).

- Reilly & Schweihs supra 386, 387. For a full discussion of discount and capitalization rates for use in IP-related valuation, see “Risk and Return: Understanding the Cost of Capital for Intellectual Property” by Glenn Perdue, les Nouvelles, June 2015.

- Shannon P. Pratt & Alina V. Niculita, Valuing A Business: The Analysis and Appraisal of Closely Held Companies, 182 (5th ed. 2008).