les Nouvelles May 2023 Articles of the Month:

This month we present two articles of the month.

Trade Marks And The Metaverse:

A European Perspective

This article will be of interest to all those who were interested in the ‘Various Legal Issues in the Metaverse’ workshop at the LESI Annual Conference in Montréal.

The Once Thought Far-Off-In-The-Future Challenges To Copyright Law Posed By Artificial Intelligence Have Arrived: And I For One—Gulp—Welcome Our New Robot Overlords

This article will be of interest to all those who were interested in the ‘AI’s Evaluation and Impact Given to the Business and Intellectual Property Law Systems’ panel discussion at the LESI Annual Conference in Montréal.

The Once Thought Far-Off-In-The-Future Challenges To Copyright Law Posed By Artificial Intelligence Have Arrived: And I For One—Gulp—Welcome Our New Robot Overlords

Partner

Wiggin and Dana LLP

New York, NY

Patent Agent

Wiggin and Dana LLP

New Haven, CT

While we are still not in the realm of sentient machines, current-day iterations of artificial intelligence (AI) are demonstrating themselves to be potential sources of creativity which are challenging our understanding of authorship in the context of intellectual property. If AI can create new content based upon its “perceptions,” how is that distinct from human authorship and furthermore, how does or how should AI fit into the current U.S. copyright landscape?

The answer to this question matters; it is no longer an academic or theoretical one, but one that must be grappled with and answered to deal with art, music, and literature that is being created right now. A few recent examples of apparent AI contributions to “original” works have included music1-3 and works of visual art.4-6 One striking example in the music space is the use of AI in 2019 to complete the unfinished Eighth Symphony by Franz Schubert based upon 90 previous compositions.2,3 A composer, Lucas Cantor, utilized the AI output as a starting point to develop two additional movements to the unfinished piece.2,3 Further examples are the thousands of Avatars that are created when fashioning NFT (non-fungible token) collections like Bored Ape Yacht Club; these collections are made by taking a set of traits and randomly assigning them in accordance with a pre-set rarity condition. While a human artist may create the traits, a machine implementing an AI algorithm creates the final images. Of course, these examples are more in line with AI-assisting a significant human creative input. But that is not always the case these days. As a recent New York Times headline confirmed, A.I.-Generated Art Is Already Transforming Creative Work: “Only a few months old, apps like DALL-E 2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion are changing how filmmakers, interior designers and other creative professionals do their jobs.”7 Indeed, the startlingly disruptive and powerful capabilities of OpenAI’s ChatGPT (Chat Generative Pre-Trained Transformer) alone have made it one of the most talked about news stories in the world since the AI chatbot launched in November of 2022.

We must then ask several questions: Can AI really “create” or author new works with de minimis, or even no human input? If the answer is currently yes, or likely yes at some point in the future, how will U.S. copyright law deal with this apparent inconsistency? (Spoiler alert: sole AI authorship is not currently allowed under U.S. Copyright Office rules.) How will AI-based creativity mesh with more specific areas of copyright, including derivative works and fair use? We address these questions below and provide our current insights on the road ahead.

How “Creative” is AI, Really?

Perhaps one of the most surprising recent news stories in the music area documented the rise and swift fall of “FN MEKA,” a virtual AI rapper that creates its own works (save the voicing of the lyrics it generates by a human voice)1 The AI rapper was signed by a major record company, Capitol Records, and apparently even imparted controversial sociopolitical issues into its works—leading to its recent firing for perpetuating stereotypes.8 You read that correctly—an AI creative entity under contract with a private company was terminated for its conduct. What a time to be alive.

In the visual arts area, a piece of fine art generated by AI was entered at the Colorado State Fair—and won first place.4 The piece, named “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial” was generated using Midjourney, one of a handful of programs such as DALL-E and Stable Diffusion, each being developed for producing art using AI. These programs typically generate new art based upon a short or detailed phrase written in prose. AI creative technologies are not limited to music or visual arts—many commercial programs for AI-assisted or AI-generated writing also already exist. As the New York Times noted in its recent article on the subject, “A.I. [has] entered the creative class. In the past few months, A.I.- based image generators like DALL-E 2, Midjourney and Stable Diffusion have made it possible for anyone to create unique, hyper- realistic images just by typing a few words into a text box.”7

If companies that are using AI to create movies, books, film scripts, newspaper articles and generative art cannot protect these creations under copyright law (and own and license them), they face a serious business problem. Indeed, for this very reason, Getty Images recently announced that it was banning all AI generated art from its platform.9

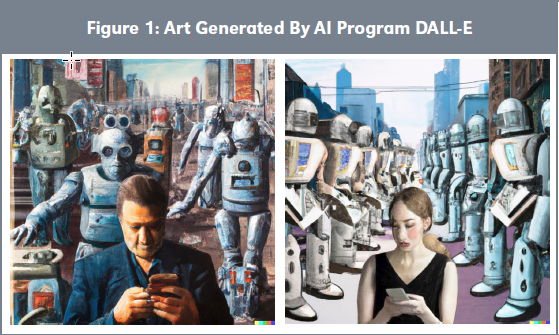

In fact, popular art-generating AI programs such as DALL-E (referred to as “generative AI” programs) are becoming so user friendly that even a complete novice can generate unique and relatively high-quality pieces of art by entering only a simple phrase as input. To illustrate this precise point (with particular emphasis on the novice aspect), we generated Figure 1 images for this article using DALL-E by entering the following italicized phrases as the only inputs: first image, left: A hyperrealist painting depicting a human surrounded by a grouping of terrifying robots in an urban landscape. The human is using a smartphone to read an article entitled: “The Once Thought Far-Off-In-The-Future Challenges to Copyright Law Posed by Artificial Intelligence Have Arrived: And I For One Welcome Our New Robot Overlords”; second image, right: A woman surrounded by a grouping of authoritative robots in an urban landscape. She is using a smartphone to read an article entitled: “The Once Thought Far-Off-The-Future Challenges to Copyright Law Posed by Artificial Intelligence Have Arrived: And I For One Welcome Our New Robot Overlords.” No special modifications or adjustments were made to the default algorithm. All that the authors did as human creatives was supply the above phrases; AI generated every other aspect of the pieces from that input.

Another popular generative AI app, Wonder, advertises by displaying the below picture with the caption “I asked Wonder app to paint ‘Pink elephant playing monopoly.’” See Figure 2.

Wonder is also capable of rendering famous paintings, like Vermeer’s “Girl with the Pearl Earring” in the styles of different painters.10

Still further questions arise. Where does all this land with respect to authorship of copyrightable work product? Should some minimum amount of artistic input be needed from a human?

It should come as no surprise that the issue of authorship rights in computer-generated works, including AI-generated works, has been analyzed in the past. For example, in a 1986 article, Professor Pamela Samuelson argued that allocating rights to the user of the computer program is the solution most compatible with U.S. Copyright law.11 It is certainly possible that Prof. Samuelson got it right over 35 years ago, as automatic allocation of rights to the AI operator would be somewhat clear-cut, at least on its face.

But with the improvement of AI technologies to their current state, and with near certainty that the pace of such improvements will only continue to accelerate, we are now faced with the reality that the AI operator can claim authorship for, arguably, a work generated with de minimis human input. That is, a policy issue surrounding this proposition appears to be whether society is willing to accept that human input is not a required ingredient in a copyrighted work. The underlying question, of course, is whether courts will find it constitutional for an author to receive exclusive rights to “writings and discoveries” that are not technically “theirs.” While assuming absolutely no human input in a work is somewhat of a simplification for the purposes of discussion, it is arguably already possible. This seems to suggest that automatically allocating rights to the AI operator may not always be feasible.

Ownership of AI-Generated Works

A separate issue to keep an eye on, aside from authorship and copyrightability, is ownership. For example, if you use a generative AI app like DALL-E or Wonder to generate a painting or some other digital work, who owns it: you or the software company? This depends on the terms of use for the software. So read those terms of use carefully, because each program will have its own, distinct terms.

For example, users who agree to use DALL-E or DALL-E 2 must first sign OpenAI’s Terms of Use. As of mid-2022, the Terms apparently indicated that OpenAI owned the generated content.12 However, as of January 2023, the Terms appear to have been amended. According to the current Terms, the “Input” that the user provides and the “Output” that the AI provides, are collectively the “Content.” The Terms indicate that the user owns the Input, and that OpenAI assigns to the user all its right, title and interest in and to the Output. The terms also include a clause—“[y]ou are responsible for Content, including for ensuring that it does not violate any applicable law or these Terms.”

Similarly, OpenAI currently allows users of ChatGPT broad personal and commercial use rights. The critical limitations are prohibitions on reverse engineering ChatGPT, using the services in a way that infringes someone else’s rights, using the services to compete with OpenAI, extracting data from the services, and on buying, selling, or transferring API keys.13 https://www.traverselegal.com/blog/can-you-use-chatgpt/.

The reader should be aware that the Terms could be subject to further changes and should always be reviewed in their current form.

Current and Future Issues at the U.S. Copyright Office

Currently, there is no way to definitively predict whether or not a piece of work containing AI-generated content will be eligible for copyright in the U.S. There was recently hope inspired that AI-assisted works which are paired with human creativity are subject to copyright registration. On September 15, 2022, the U.S. Copyright Office issued what was apparently to be the first copyright registration for an AI-generated work, in this case a comic book “latent diffusion” piece named Zarya of the Dawn.14 The graphic art in this case was AI-generated, but the human author wrote the story and made the overall artistic arrangement as a comic book. However, the U.S. Copyright Office recently initiated proceedings to revoke the copyright and the (human) author appealed the decision.15 On February 23, 2023, the Copyright Office issued a decision revoking the original copyright. The Office concluded that the human author is the legal author of the text, as well as the selection, coordination, and arrangement of the work’s written and visual elements. However, the Office determined that the AI-generated images are not the product of human authorship and cannot be protected by copyright. The Office’s solution? The author should have disclaimed any AI-generated content. The Office indicated that it will reissue a new copyright covering only the material created without AI (i.e., granting copyright registration on the overall work, but excluding copyright registrations on the art).

As will be explained in the following, the U.S. Copyright Office has taken a hard stance against solely AI-generated works, and has now taken an equally hard stance against AI-generated portions of an overall work, but it is difficult to predict where the line is when there is an ingredient of AI involved. For example, if the AI-generated ingredient is difficult to separate from the human contributions. Still, the distinction between fully AI-generated pieces and AI-assisted pieces is an important one, and may play a role in considering whether a copyright may be awarded when human creativity or input does not meet some certain, yet currently unknown, threshold. But where is the line, and can a fully or almost fully AI-generated work be registered for copyright in the U.S.?

The most current and prominent case study we have relates to the Device for the Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience (DABUS), which was created by Dr. Stephen Thaler of Missouri-based Imagination Engines Incorporated. Dr. Thaler was a party in legal proceedings for both patent and copyright works allegedly created by DABUS without any human inventorship or authorship, respectively.5-6, 16 On the patent side, in August of 2022 a Federal Circuit panel pronounced that the Patent Act unambiguously requires the naming of a human inventor, rendering DABUS’ alleged invention simply unpatentable as submitted.16 The Federal Circuit found that resolving the issue did not require “an abstract inquiry into the nature of the invention or the rights, if any, of AI systems.” Rather, the decision was based only on the language of the Patent Act, which defines inventors as “individuals,” a term that legal precedent has interpreted to refer to a natural person. The court concluded that “the Patent Act, when considered in its entirety, confirms that ‘inventors’ must be human beings.” Dr. Thaler has not been successful in any jurisdiction in his arguments to the contrary, with the exception of South Africa, which granted the first (and currently only) patent to an exclusively AI inventor.17

Most recently, the full Federal Circuit recently ruled that it would not take up Dr. Thaler’s petition for en banc review, thereby ending his bid to name the artificial intelligence machine he created as an inventor on the two patents at issue.18 The short order did not include any reasoning. This is a significant issue with interesting implications on the patent side, especially as we rely more on sophisticated AI in the business of, for example, drug discovery and other innovation research.13

On the copyright side, DABUS is said (by Dr. Thaler) to have created a 2D visual work called “A Recent Entrance to Paradise,” which was refused registration by the U.S. Copyright Office for not naming a human author. On June 2, 2022, Dr. Thaler filed a complaint in the U.S. District Court of Washington D.C. after final rejection at the U.S. Copyright Office.6,19 The complaint includes several arguments, including that the plain language of the Copyright Act (Title 17 U.S.C.) allows protection of AI-generated works, that no case law disallows copyright of AI-generated works, that AI authorship is constitutional, that Dr. Thaler is entitled to the work under certain rules of property ownership and/or work for hire, and that “…corporations and other non-human entities have been considered ‘authors’ for purposes of the Act for over a century. 17 U.S.C. § 101.” The most recent activity is Dr. Thaler’s January 2023 motion for summary judgment, in which he argues 1) that neither the Copyright Act nor the case law restricts copyright to human-made works and 2) that the work-for-hire doctrine is consistent with Dr. Thaler properly owning a copyright for the creation by DABUS, an “employee” for the purposes of the doctrine, and, alternatively or additionally, that Dr. Thaler’s ownership can be established by virtue of the property law principles of property begetting property or first possession. It should be noted that Dr. Thaler’s situation might not apply to many prospective owners of AI-produced materials. That is, his development and ownership of the AI itself might present the court with an opportunity to limit its decision, should it bite on any of Dr. Thaler’s arguments.20

While it is not our aim to fully evaluate the merits of the arguments here, the question of whether the plain language of the Copyright Act (Title 17 U.S.C.) allows for protection of AI-generated works is certainly ripe for debate. The U.S. Copyright Office, in its Compendium of regulations,21 currently interprets the relevant statute (17 U.S.C. § 102) to include only human “authors.” The answer, however, lies in the interpretation of the Copyright Act and/or the U.S. Constitution. Article I, Section 8, Clause 8 of the U.S. Constitution grants Congress the power “[t]o promote the progress of science and useful arts, by securing for limited times to authors and inventors the exclusive right to their respective writings and discoveries.” Interpretation of “authors and inventors” is central to the ongoing discussions regarding rights for creative AI, if any. The Copyright Act provides that “[c]opyright protection subsists, in accordance with this title, in original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device…”17 U.S.C. § 102(a).

Therefore, a question exists as to the meaning of “original works of authorship,” and particularly as to the meaning of authorship in U.S. copyright law. If “authors” as recited in the U.S. Constitution and “authorship” as recited in the Copyright Act are each interpreted to include non-human creative entities such as AI, then the answer to the question of AI authorship appears clear. This interpretation would go hand-inhand with Dr. Thaler’s argument that AI authorship is constitutional and permitted under the Copyright Act.

On the other hand, if the courts deem AI authorship to be unconstitutional, or alternatively hold that Congress did not confer AI authorship under the Copyright Statute, all AI-created works without a human author may end up in the public domain. This outcome would arguably be at odds with both public and economic policy and the underlying view of the Framers -- that securing exclusive rights is “[t]o promote the progress of… useful arts.” Putting aside the man vs. machine policy implications, it seems hard to argue that AI creativity is not “useful.” By way of example, AI can potentially outcompete human artists as judged by human judges, as was explained above with respect to the “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial” piece. However, the counterargument, as grounded in the current statute, remains that AI never arises to anything more than “…a machine or device” aiding a human “artist,” and does not account for the amount of contribution by the human compared to the machine or device. This interpretation also seems problematic, in that it devalues and overlooks that the brunt of the creative work is being performed by an entity other than the human “artist.” For example, should the authors of this article, rightly be considered “authors” of the cover images that AI generated based only on a few keystrokes’ worth of our creative effort and input?

A thought experiment that crystallizes the issue further asks the following hypothetical: what if AI (or even a non-AI random phrase generator) generates the prompt that is input into another AI, such as DALL-E, to generate a new visual work? An input phrase could be useful to generate new art even if it has not been proofread or ever viewed by a human in any way. Does a human’s effort of selecting a solely AI-generated piece that they view as appealing amongst a library of generated pieces count toward authorship in any way? These are the types of issues that copyright law will inevitably be forced to address.

The Question of Whether an AI Created Work is a Derivative Work

Apart from the question of whether AI or AI-assisted works are protectable by copyright, there is a separate interesting, and important, question of whether AI-created works that are derived from analyzing existing works or styles would require a license from the original author to avoid a claim of copyright infringement.

Under the U.S. Copyright Act, a “derivative work” is any work which, as a whole, represents an original work of authorship but contains additional authorship of new creative material.22 For example, a piece of digital art, or a composition, may resemble or draw upon recognizable aspects of a prior copyrighted work, but may adapt it or add new aspects which are distinct from the prior copyrighted work. The author of such a derivative work infringes any prior copyrighted work if used without permission. Of course, public domain material may be incorporated into new works without permission.

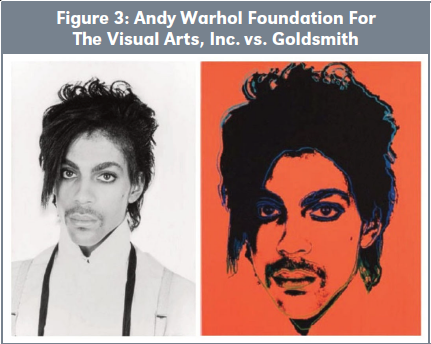

There are also complex issues that must be sorted out as to when the new work “transforms” the old work and would qualify as fair use. The question of when a piece of art is a derivative work and when it is a transformative fair use is at issue before the U.S. Supreme Court in the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 21-869 (U.S.) case. At issue there is whether an Andy Warhol illustration of the rock star Prince (right) is an infringement or a transformative fair use, when it was based on a photograph of Prince taken by rock and roll photographer, Lynn Goldsmith (left).23 See Figure 3.

This aspect of copyright law raises a particular challenge for AI-based creative entities:

What makes the new breed of A.I. tools different, some critics believe, is not just that they’re capable of producing beautiful works of art with minimal effort. It’s how they work. Apps like DALL-E 2 and Midjourney are built by scraping millions of images from the open web, then teaching algorithms to recognize patterns and relationships in those images and generate new ones in the same style. That means that artists who upload their works to the internet may be unwittingly helping to train their algorithmic competitors.24

Because AI utilizes expansive sets of training data in order to produce a work product, there is a risk that the AI-produced work could be considered to be an infringing derivative work if the training data included any copyrighted material. In infringement proceedings, this would be a question for the finder of fact as to whether or not the work, as a whole, represents the original work, or copyrighted material, and when and whether fair use applies.

Delving a bit deeper into the underlying principles of AI is instructive toward this point. At a very high level, AI operates using neural networks, which are artificial representations of neurons, to mimic or approximate human thought. The networks generally make connections and correlations between large sets of input data and produce outputs based upon those correlations. Their structure, i.e., the portions in-between the input and output, is dynamic and adapts based upon a process called “training,” where the AI “learns” how to interpret input “training data” with active oversight or validation. Depending upon the complexity of the output, the size of the input training data set, and many other factors, the training can be an intensive process to produce an eventually refined AI such as DALL-E.

Thus, all AI-produced work products are algorithmically derivative in some sense by virtue of AI operating principles. In the context of visual arts, the final product could potentially be a derivative work if an original work was included in the training data. If the training data set is large enough, there could arguably be a “dilution effect”—in this case it is unlikely that the AI-produced work product would, as a whole, represent any copyrighted original work in the training set. However, in instances where the AI work product does potentially, as a whole, represent any copyrighted original work, one might only need to look to the training data to conclusively prove infringement. On the flip side, assuming absolutely no human input, wouldn’t a creative product by AI utilizing only public domain training data be conclusively non-infringing as to any coincidentally similar works? Since copyright infringement requires copying, there could seemingly be no infringement if only public domain works are included in the training data. There are differing viewpoints on the impacts of training data including copyrighted material, such as it being covered under the umbrella of fair use from a legal standpoint.25 Copyright holders who feel copied may have a different opinion, which may or may not be legally supported.

Another difficult question could be whether or not copying an artist’s style rather than the artist’s works could constitute copyright infringement in the world of AI. If DALL-E is told to create art in the style of Dalí, would hypothetical copyright infringement exist where the AI-produced product does not directly resemble any of Dalí’s works, but closely or impeccably copies the artist’s style based upon its training data? This is not a theoretical question. AI has already been trained in the style of Rembrandt by digesting and analyzing the data corresponding to all of the master’s paintings and used to create new “Rembrandts” (painted by an AI aptly named ‘The Next Rembrandt’) as well as to repair old ones.26, 27 It is also interesting to note that artistic style is not necessarily restricted to visual works. For example, AI has been used to write lyrics mimicking musical artist Nick Cave’s lyrical style.28 (Cave thought those lyrics “sucked” and that you need a human soul and to have experienced human suffering to write good lyrics). Perhaps more in line with parody, rapper Snoop Dogg’s style has been copied to write a rap about breakfast cereals— although the pertinent legal questions still equally apply.29 Text-based AI such as ChatGPT are used in these instances (more on this below).

While important in its own right to IP holders, there is more at stake here than the copying of historical figures’ iconic styles. Living artists relying upon their creative style—developed over a lifetime of hard work to reach a point of recognition—have already been subjected to their style being copied by AI.30 It seems that the algorithmic nature of AI might allow copying of style with a level of surgical precision not possible by a human imitator who would unconsciously impart their own stylings. Thus, copyright law will likely need to reckon with cases where a work is not copied, but a style is, indeed, copied and not just imitated.

ChatGPT

Another AI entity deserving its own section here for bursting on the scene and becoming a massive standalone part of the AI zeitgeist is ChatGPT—OpenAI’s chatbot that, despite its name, does a lot more than simply chatting with the user. In fact, in the wake of laying off 10,000 workers due to economic uncertainties and prioritization of AI initiatives, Microsoft is set to invest $10 billion in OpenAI, seeking a 49 percent stake.31,32

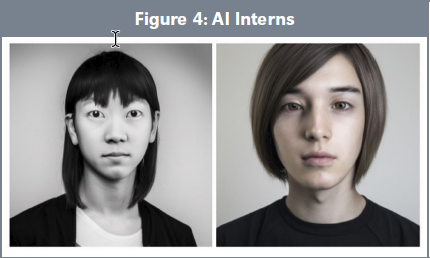

Above, we cited two examples of ChatGPT copying musical artists’ lyrical styles, which is likely in the realm of copyright. However, the impacts of this AI will be far-reaching, as noted in the following examples showing how disruptive this technology truly is. Schools and universities are being forced to implement blocks or even reconsider their entire curricula in view of the capabilities of this AI to fluently write entire essays.33 ChatGPT has been researched for its ability to take the Bar exam required for attorney admission—while it has not yet passed, it was optimized to achieve a correct rate of about 50 percent, which is much higher than the guess rate of 25 percent, and it did pass and in fact did quite well in two specific areas of law.34 Stack Overflow, an indispensable resource blog for computer programmers, has now (temporarily) banned ChatGPT-generated submissions.35 One of the stranger stories in this space involves Codeword’s “AI interns” which it employed this winter.36 With prompting from their managers, the interns selected their own names and visual presentations (see photos below of Aiko (left) and Aiden (right)). Tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney, and Dall-E 2 were apparently used thus far in the interns’ “employment.”

While the examples in Figure 4, tend to focus on the more shocking and disruptive aspects of these technologies, there are many potentially positive impacts. If used appropriately, tools such as ChatGPT could be used to efficiently improve, but not replace, human efforts.37 This comes hand-in-hand with the idea that AI will lead to a major shift in career roles, but likely will not (fully) replace workers in the artistry and knowledge sectors.38 Of course, only time will tell what the impact of these technologies will truly be.

Recent IP Lawsuits Regarding AI

A first wave of lawsuits against AI-makers have been filed in recent months kicking off the beginning of the so-called AI Wars in the courts. If litigated, these early suits will give the courts an opportunity to consider some of the complex issues at play. One fundamental question implicated by these lawsuits is whether artists and content creators have the right to authorize or block AI systems from collecting and using their content as training data, whether under copyright law or some other doctrine.

First, in Andersen et al. v. Stable AI Ltd., et al., No. 23 Civ. 201 (N.D. Cal. Jan. 13, 2023), a putative class action copyright infringement lawsuit was brought in the Northern District of California by several artists against a number of generative AI app-makers, including Stable AI (the maker of the Stable Diffusion app), Midjourney, and Deviant Art (which makes the DreamUp app). The causes of action include claims of direct copyright infringement, vicarious infringement, DMCA violations (for the removal of copyright management information), California right of publicity and related unfair competition claims. In the main, the Complaint alleges that the defendants’ AI apps use the works of the plaintiffs without permission to train AI through machine learning to create new AI-generated works, some of which constitute infringing derivative works. The Complaint frames these apps as “21st century collage tools that violate the rights of millions of artists.” Interestingly, the allegations focus on the ability of these generative AI apps to create art “in the style of” a particular artist based on art by that artist that was included in its training data set. Plaintiffs argue that the output of these generative art apps are unlicensed derivative works.

While the Defendants have not yet responded to the Complaint, which just filed in mid-January, there are a number of substantive complexities with these claims on the merits. First, it is unclear that the “collage” metaphor is factually correct or that any actual copies of the copyrighted works are stored by the Defendants. Second, it is far from clear that “style” is protectable by copyright. Third, Defendants are sure to argue that the output of their apps is a transformative work that bears little to no similarity to any one artist’s work and therefore is a non-infringing fair use.

Another issue that is sure to draw focus in these AI lawsuits is the training data sets that the AI apps use as input for their machine learning. In the Andersen case, the training data is alleged to come from a German project called Large-Scale AI Open Network (LAION), which allegedly pulls data from large sets of copyrighted data like Getty Images and Shutterstock. In an era of machine learning, these data sets are going to be extremely valuable, and the ability to control, license and monetize is critical.

There will surely be both business deals and disputes over who should profit from and share profits from its monetization. For example, in early January 2023, Shutterstock and Meta announced such a deal, following on the heels of a similar deal with OpenAI.39 On the other hand, on January 17, Getty sued Stability AI in the UK, with claims for copyright infringement and unlawful web scraping, arguing that instead of licensing their content for training purposes, “Stability AI unlawfully copied and processed millions of images protected by copyright and the associated metadata owned or represented by Getty Images absent a license to benefit Stability AI’s commercial interests and to the detriment of the content creators.” Most recently, on February 3, Getty escalated its dispute with Stability AI by also suing in the U.S. in the District of Delaware, asserting both copyright and trademark infringement claims. Getty Images alleges that “Stability AI has copied more than 12 million photographs from Getty Images’ collection, along with the associated captions and metadata, without permission from or compensation” in order to build a competing business “on the back of intellectual property owned by Getty Images and other copyright holders.”

Indeed, the issue of web scraping and the extent to which companies can control who can access materials via website terms and conditions or contract law is an issue that might be shortly taken up by the U.S. Supreme Court in the ML Genius Holdings LLC v. Google LLC case. In a dispute between the lyrics posting website, Rap Genius sued the well-known search engine for scraping and displaying its lyrics in search results, allegedly in violation of Rap Genius’s terms of service. Significantly, Rap Genius did not (and could not) sue Google for copyright infringement because Rap Genius does not hold the copyright to the underlying lyrics. However, the Rap Genius terms of service prohibit users from commercially reproducing or distributing any portion of the posted content. The Second Circuit held that copyright law preempted Rap Genius’s claim for breach, finding the breach claim was not “qualitatively different from a copyright claim.”

International Responses to AI

In considering how or whether U.S. policymakers, law makers, regulators, and government agencies might respond, it may be instructive to consider how other countries have handled the issue of computer-generated works.

In the UK, for example, a special form of copyright protection is available for original literary, dramatic, musical, or artistic works generated solely by a computer or AI. Such special copyrights in the UK enjoy a reduced 50-year term compared to the 70-year term for a work containing some degree of human authorship. The copyright is granted to the person who developed the computer program.40 Indian law currently contains a provision from 1994 that the author of a computer- generated literary, dramatic, musical, or artistic work is the person who causes the work to be created.41 New Zealand has taken a similar stance, that the computer- generated work is authored by the person who “makes the necessary arrangements for the creation of the work.”42 The law in each of India and New Zealand might also, as in the UK, include programmers or persons who arguably had no creative input. Most other countries, however, do not have any clear provisions for copyrighting computer-generated works.

The Italian Supreme Court recently issued a decision in a case involving the issue of whether digital artwork is copyrightable. In its decision, the court prescribed an assessment of whether, and to what extent, the use of the software tool absorbed the creative elaboration of the artist who used it.43 This judicial approach is an interesting one because it gets at the issue of whether some de minimis human input is necessary for a copyrighted work—or whether courts could look to this factor.

There are also questions of whether the data mining aspect of AI technologies is covered under existing laws. While we have highlighted the fair use aspects in the U.S., do potentially relevant legal constructs in other jurisdictions exist currently? Particularly, the European Union does not recognize a fair use doctrine and, instead, has specific copyright regulations in its EU Directives. For example, the EU’s Digital Single Marketplace directive (DSM) has been examined in respect to this important topic.44 While no express rights are granted or denied, the Directive has exception language directed to text and data mining, such as automated analysis of data to generate information including patterns, trends, and correlations within data sets. (Article 2(2) of the DSM Directive). At least to the informed layman, these activities sound eerily similar to the underlying processes of machine learning.

While also not immediately related to the registration of copyrighted works, there have been interesting developments in China’s response to AI-created works. New regulations, which took effect in January 2023, require that any AI-generated media include an identifying watermark.45 While it appears that the watermarks are only applicable to AI-generated images and “deep fakes,” this move signals a coordinated government response to separate AI-produced content from human-produced content. In another step to regulate digital markets, China has also launched a state-sanctioned NFT and digital collectibles trading platform.46 From these steps, it appears that, perhaps unsurprisingly, the authoritarian approach to digital intellectual property and AI-generated content will be tight regulation.

It will certainly be instructive to follow whether or not strategies to regulate AI media will ultimately be effective—there remains the practical question of whether it is even possible to police massive amounts of AI-generated material. The options at this time appear to be a highly distributed ledger system that carries trusted assertions about provenance, a clone army of AI fact checkers, or a fight-fire-with-fire intelligent (AI) approach.47 The latter is being developed for ChatGPT outputs, in the form of the AI-detecting program GPTZero. We are not programmers, but it seems that these detection algorithms will likely be immediately useful to detect AI outputs and will subsequently be useful to train the next version of AI which avoids detection. This point aside, OpenAI has itself now released a tool to detect machine-written text in response to the growing concerns surrounding these technologies.49

While it is highly unlikely that there will be a onesize- fits-all approach with respect to international copyright law for AI-generated work products, it will be informative to follow any developments internationally as other nations grapple with how to proceed.

An Unpredictable Future for U.S. Copyright

Assuming there is no constitutional bar to AI authorship (which is not a certainty, but remains an unsettled question), there appear to be the following options for policymakers, ranked (with no sarcasm intended) by order of likelihood:

- Do Nothing. Common law, as set forth by the courts, will dictate interpretation of the current statute. Here, we could let the courts work out disputes over copyright eligibility for AI, copyright infringement assertions and anti-scraping measures for training data against AI apps under the current statutes. If recent caselaw from the patent law side of the aisle is to be any guide, it is likely that courts will continue to find that AI will not be eligible as the author of a work. Therefore, any such AI-generated works would be public domain. AI-assisted works, having some degree of human input, may be registerable for copyright, but the courts may need to draw a line to determine a minimum threshold for human contribution to constitute authorship.

- Amend or Pass New Statute. Congress could specifically include or exclude AI as creative authors, or could state that authors must be human. However, if excluded, and an AI does create an original work to an extent that the human does not feel that they have contributed, it would be fraudulent for the human to claim authorship. The work would either be public domain or would be the product of fraud on the U.S. Copyright Office if registered with false authorship information. Congress could also pass more specific legislation focused on IP issues including AI’s use of training data.

- Adjust U.S. Copyright Office and U.S. Policy. With no clear pronouncement yet in place from the courts in the context of modern AI, or if the courts refuse to create precedent for any of the outstanding issues, the U.S. Copyright Office could technically, in its role of administering copyright law, make its own interpretation as to those issues. Again, at this time, as per current Copyright Office guidance, AI cannot be a sole author. It would take a policy directive from the top to change this.

- Wait for Somebody to Develop HAMILTON-E. AI-generated statute or AI-assisted statute drafting could potentially take into account the multi- faceted and complex issues surrounding AI and intellectual property. We could even ask ChatGPT to start this process and see what it comes up with! (The authors do not actually propose this option).

A quote by Stanford Law Professor Mark Lemley rather aptly captures some of the subtlety and complexity of some of the issues discussed above:

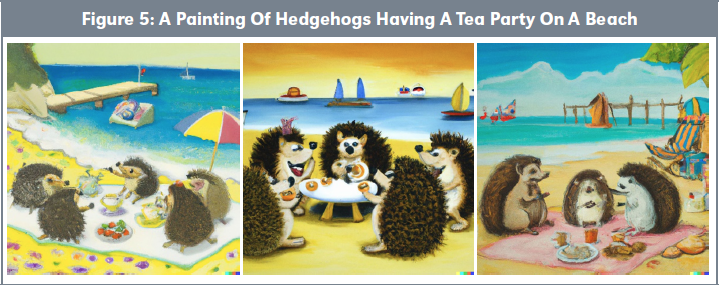

“If I ask Dall-E to produce a painting of hedgehogs having a tea party on a beach, I have contributed nothing more than an idea. Dall-E generates the art that aligns with that idea. True, individual elements of that art are generated based on Dall-E’s database of all existing art, but no more-than-de-minimis element of an existing piece of art is likely to show up in what Dall-E produces. I think looking for a human “author” in that scenario is fruitless. It is an effort to bend reality to match the legal categories we have already created. That doesn’t mean we have to declare Dall-E an artist and therefore give it a copyright. But it does mean that no human artist has a legitimate claim to be an author under existing law. We may be fine with that and say that this work has no author and so enters the public domain. Or we may want it to be owned by someone for some reason. But if we make the latter choice, we are changing our definition of authorship.”

Speaking of which, thank you Professor Lemley for the idea for the 11-word prompt “a painting of hedgehogs having a tea party on a beach,” and thank you DALL-E for the rest. See Figure 5.

We don’t aim to offer a solution for the broad set of complicated issues discussed herein. But the related uncertainties in this emerging space leads to significant business risks related to AI-generated or AI-assisted work products. With such risk comes untapped economic potential for which a solution would be desirable sooner rather than later from our policymakers. At any rate, the future is both uncertain, but equally exciting, and is also sure to become only more interesting as our robot overlords slowly assume their role.

Conclusion

In view of this rapidly developing area of technology, commercialization strategies must consider the associated uncertainties in how intellectual property law will deal with the new reality of AI-generated creative works. It is important to confront this issue in the near term because AI that is pushing the margins on these issues is now here and in real form in the marketplace today, and it’s a complex issue at the margins. As a policy matter, it will be important to consider how the law should work here, and to get it right, because this is a significant issue in terms of investment and protection for the art and technology spaces.

Currently, the U.S. Copyright Office does not, as a matter of policy, grant copyrights to works produced solely by AI with no human author. While some degree of human contribution to an otherwise copyrightable work product produced by AI may potentially be sufficient, there is no specific guidance as to how much contribution is required. Likewise, there is no guidance as to whether or not a copyright registration may be challenged on the basis of lacking human authorship, or whether and when an AI-trained algorithm creates an infringing derivative work when it imitates the style of a particular artist or “learns” based on an existing artistic oeuvre.

We expect further interesting developments in this area as the law continues to confront new and evolving AI technologies. The one certainty is that AI creative entities are here to stay and will have more—not less— of a role in creating art, music, and literature. The intersection of these issues and how and whether policymakers address them will continue to pose important and complicated questions. ■

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): https://ssrn.com/abstract=4352059.

- Fitzgerald, T. “Virtual Rapper FN Meka Powered By Artificial Intelligence Signs to Major Label” XXL Magazine, August 21, 2022, URL: https://www.xxlmag.com/fn-meka-virtual-rapper-signs-major-label.

- Hunn, M. “Musician vs. Machine: Is AI-Generated Music the Sound of the Future?” NEWM, August 31, 2022, URL: https://newm.io/musician-vs-machine-is-ai-generated-music-the-sound-of-the-future/.

- Bennett II, J. “An AI Just Finished Shubert’s ‘Unfinished’ Symphony” WQXR Editorial, March 1, 2019, URL: https://www.wqxr.org/story/ai-just-finished-schuberts-unfinished-symphony/.

- Gault, M. “An AI-Generated Artwork Won First Place at a State Fair Fine Arts Competition, and Artists are Pissed” Vice, August 31, 2022, URL: https:// www.vice.com/en/article/bvmvqm/an-ai-generatedartwork-won-first-place-at-a-state-fair-fine-arts-competition-and-artists-are-pissed.

- Feldman, J. “The art of artificial intelligence: a recent copyright law development” Reuters, April 22, 2022, URL: https://www.reuters.com/legal/ legalindustry/art-artificial-intelligence-recent-copyright-law-development-2022-04-22/.

- Graves, F. “Thaler Pursues Copyright Challenge Over Denial of AI-Generated Work Registration” IPWatchdog, June 6, 2022, URL: https://www.ipwatchdog.com/2022/06/06/thaler-pursues-copyright-challenge-denial-ai-generated-work-registration/ id=149463/.

- Roose, K. “A.I.-Generated Art is Already Transforming Creative Work” The New York Times, October 21, 2022, URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/21/ technology/ai-generated-art-jobs-dall-e-2.html?smid=nytcore-ios-share&referringSource=articleShare.

- Tracy, M. “A ‘Virtual Rapper’ Was Fired. Questions About Art and Tech Remain” The New York Times, September 6, 2022, URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/06/arts/music/fn-meka-virtual-ai-rap.html.

- Edwards, B. “Fearing copyright issues, Getty Images bans AI-generated artwork” Ars Technica, September 21, 2022, URL: https://arstechnica-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/arstechnica.com/information-technology/2022/09/fearing-copyright-issues-getty-images-bans-ai-generated-artwork/?amp=1.

- Wonder.ai, via Instragram, URL: https://www.instagram.com/reel/CjpC600KB0Y/?igshid=Ym-MyMTA2M2Y%3D.

- Samuelson, P. “Allocating Ownership Rights in Computer-Generated Works” 47 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 1207 1985-1986.

- Ellison, S., Esq. “Who Owns DALL-E Images?”, FindLaw, August 29, 2022, URL: https://www.findlaw.com/legalblogs/legally-weird/who-owns-dalle-images/.

- Schaefer, E. “Can You Use ChatGPT to Make Money?,” TraverseLegal, January 14, 2023, URL: https://www.traverselegal.com/blog/can-you-usechatgpt/.

- Edwards, B. “Artist receives first known U.S. copyright registration for latent diffusion AI art,” Ars Technica, September 22, 2022, URL: https://arstechnica-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/arstechnica.com/information-technology/2022/09/artist-receives-first-known-us-copyright-registration-for-generative-ai-art/?amp=1.

- Cronin, B. “AI-Created Comic Could Be Deemed Ineligible for Copyright Protection,” CBR.com, December 21, 2022, URL: https://www.cbr.com/ai-comic-deemed-ineligible-copyright-protection/.

- Pattengale, B. and Sabatelli, A. “Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Inventorship—Will the next blockbuster drug be denied patent protection?,” Wiggin and Dana Publication, August 17, 2022, URL: https://www.wiggin.com/publication/artificial-intelligence-ai-and-inventorship-will-the-next-blockbuster-drug-be-denied-patent-protection/.

- Karpan, A. “South Africa Issues World’s First Patent with AI Inventor,” Law360, July 28, 2021, URL: https://www.law360.com/articles/1407508/.

- Lidgett, A. “Full Fed. Circ. Won’t Consider Push To Let AI Be Inventor,” Law360, October 20, 2022, URL: https://www.law360.com/articles/1541857/.

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, District Court, D.C., Filed June 2, 2022 , URL: https://www.courtlistener.com/ docket/63356475/thaler-v-perlmutter/.

- Thaler v. Perlmutter, Plaintiff’s Motion for Summary Judgement, District Court, D.C., filed January 10, 2023, URL: https://storage.courtlistener.com/recap/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956/gov.uscourts.dcd.243956.16.0.pdf.

- The Regulations state: “Section 102(a) of the Copyright Act states that copyright protection extends only to “original works of authorship.” Works that have not been fixed in a tangible medium of expression, works that have not been created by a human being, and works that are not eligible for copyright protection in the United States do not satisfy this requirement.” Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices, 3rd edition, Ch. 700, S. 707.

- A “derivative work” is a work based upon one or more preexisting works, such as a translation, musical arrangement, dramatization, fictionalization, motion picture version, sound recording, art reproduction, abridgment, condensation, or any other form in which a work may be recast, transformed, or adapted. A work consisting of editorial revisions, annotations, elaborations, or other modifications which, as a whole, represent an original work of authorship, is a “derivative work.” 17 USC § 101.

- Szynol, P. “The Andy Warhol Case That Could Wreck American Art,” The Atlantic, October 1, 2022, URL: https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/ archive/2022/10/warhol-copyright-fair-use-supremecourt-prince/671599/.

- Roose, K. “An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy,” The New York Times, September 2, 2022, URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/02/technology/ai-artificial-intelligence-artists.html.

- Lemley, M.A. et al. “Fair Learning,” Texas Law Review, Vol. 88, Issue 4, 2021, URL: https://texaslawreview.org/fair-learning/.

- Brinkhof, T. “How to Paint Like Rembrandt, According to Artificial Intelligence,” Discover Magazine, August 23, 2021, URL: https://www.discovermagazine.com/technology/how-to-paint-like-rembrandt-according-to-artificial-intelligence.

- Mattei, S. “Artificial Intelligence Restores Mutilated Rembrandt Painting ‘The Night Watch’,” ARTnews, June 23, 2021, URL: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/rembrandt-ai-restoration-1234596736/.

- Savage, M. “Nick Cave says ChatGPT’s AI attempt to write Nick Cave lyrics ‘sucks’,” BBC News, January 17, 2023, URL: https://www.bbc.com/ news/entertainment-arts-64302944.

- Anonymous, “The rap it [ChatGPT] created in the style of Snoop Dogg. But is it copyright infringement?,” ChatGPT Is Eating The World, January 12, 2023, URL: https://chatgptiseatingtheworld.com/2023/01/12/chatgpt-is-eating-the-world-the-rapit-created-in-the-style-of-snoop-dogg-but-is-it-copyrightinfringement/).

- Nolan, B. “Artists say AI image generators are copying their style to make thousands of new images— and its completely out of their control,” Business Insider, October 17, 2022, URL: https://www.businessinsider.com/ai-image-generators-artists-copying-style-thousands-images-2022-10.

- Browne, R. “Microsoft reportedly plans to invest $10 billion in creator of buzzy A.I. tool ChatGPT,” CNBC, January 10, 2023, URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/10/microsoft-to-invest-10-billion-inchatgpt-creator-openai-report-says.html .

- Weise, K. “Microsoft to Lay Off 10,000 Workers as it Looks to Trim Costs,” The New York Times, January 18, 2023, URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/18/business/microsoft-layoffs.html.

- Huang, K. “Alarmed by A.I. Chatbots, Universities Start Revamping How They Teach,” The New York Times, January 16, 2023, URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/16/technology/chatgpt-artificial-intelligence-universities.html.

- Bommarito, M.J. et al. “GPT Takes the Bar Exam,” SSRN, December 31, 2022, URL: https:// papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_ id=4314839.

- Marcus, G. et al. “AI’s Jurassic Park Moment,” Communications of the ACM, December 12, 2022, URL: https://cacm.acm.org/blogs/blog-cacm/ 267674-ais-jurassic-park-moment/fulltext.

- Monson, K. “Introducing our first AI interns, Aiko and Aiden,” Medium, January 11, 2023, URL: https://medium.com/cover-story/introducing-our-first-ai-interns-aiko-and-aiden-75d3bfea2bc4.

- Chen, Brian X. “How to Use ChatGPT and Still Be a Good Person,” The New York Times, December 21, 2022, URL: https://www.nytimes. com/2022/12/21/technology/personaltech/how-touse-chatgpt-ethically.html.

- Parker, L. et al. “AI and the future of work: 5 experts on what ChatGPT, DALL-E and other AI tools mean for artists and knowledge workers,” The Conversation, January 11, 2023, URL: https://theconversation.com/ai-and-the-future-of-work-5-expertson-what-chatgpt-dall-e-and-other-ai-tools-mean-for-artists-and-knowledge-workers-196783.

- Shutterstock, Inc. “Shutterstock Expands Long-standing Relationship with Meta,” PR Newswire, January 12, 2023, URL: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/shutterstock-expands-long-standing-relationship-with-meta-301719769.html.

- Yaros, O. et al. “UK Government’s consultation on artificial intelligence and the interaction with copyright and patents,” Mayer Brown, December 1, 2021, URL: https://www.mayerbrown.com/ en/perspectives-events/publications/2021/12/ uk-governments-consultation-on-artificial-intelligence-and-the-interaction-with-copyright-and-patents.

- Verma, A. et al. “Copyright authorship to artificial intelligence: Who owns it?,” Lakshmikumaran & Sridharan attorneys, May 17, 2022, URL: https:// www.lakshmisri.com/insights/articles/copyright-authorship-to-artificial-intelligence-who-owns-it/.

- Jackson, G. “Artificial Authorship in New Zealand: is the law equipped?,” James & Wells, October 22, 2019, URL: https://www.jamesandwells.com/intl/artificial-authorship-in-new-zealand-is-the-law-equipped/#:~:text=In%20New%20 Zealand%2C%20a%20computer,to%20another%20 person%20or%20entity.

- Stein, A.M. “Digital art protectable under copyright? Yes, says the Italian Supreme Court,” The IPKat, February 3, 2023, URL: https://ipkitten.blogspot.com/2023/02/digital-art-protectable-under-copyright.html.

- Nordemann, J.B. et al. “Copyright exceptions for AI training data—will there be an international level playing field?,” Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice, Vol. 17, Issue 12, December 2022, pp. 973—974, URL: https://academic.oup.com/jiplp/ article/17/12/973/6880991.

- Edwards, B. “China bans AI-generated media without watermarks,” ARS Technica, December 12, 2022, URL: https://arstechnica.com/information-technology/2022/12/china-bans-ai-generated-media-without-watermarks/).

- Ledger Insights, “China launches national digital asset exchange for NFTs, metaverse,” Ledger Insights, January 3, 2023, URL: https://www.ledgerinsights.com/china-national-digital-asset-exchange-nfts-metaverse/.

- Shamoon, T. “The Irritation Game,” Trust Rubicon, January 7, 2023, URL: https://talalshamoon.substack.com/p/the-irritation-game.

- Bowman, E. “A college student created an app that can tell whether AI wrote an essay,” NPR, January 8, 2023, URL: https://www.npr.org/2023/01/09/1147549845/gptzero-ai-chatgptedward-tian-plagiarism.

- Fried, I. “OpenAI releases tool to detect machine- written text,” Axios, January 21, 2023, URL: https://www.axios.com/2023/01/31/openaichatgpt-detector-tool-machine-written-text.