les Nouvelles October 2015 Article of the Month

Risk And Return: Understanding The Cost Of Capital For Intellectual Property Part 1 of 2

Glenn Perdue

Glenn Perdue

Kraft Analytics LLC,

Managing Member,

Nashville, TN

I. Introduction

Human beings are hardwired to assess risk and return. Whether driving faster to avoid being late for a meeting or demanding more equity to invest in a deal, we constantly consider the tradeoffs between risk and what we stand to gain by accepting that risk.1

When contemplating transactions or damages involving intellectual property (IP) we often assess risk and return through the use of income-based analysis that considers future benefits, costs, and uncertainty. If we are determining a present value through discounted cash flow analysis, the selection of an appropriate discount rate is a critical element.

Relying on established concepts and approaches from economics and finance, this paper will explore the cost of capital for IP. The term “cost of capital” as used herein is synonymous with other terms such as opportunity cost of capital, required return, expected return, and discount rate, all of which refer to the same basic idea: a cost for the use of capital that is market-based and risk-adjusted.

II. Income Approach Basics

In valuing assets we use cost, market and incomebased approaches.

Cost-based approaches consider the cost to obtain a replica or functional equivalent of the subject asset as a basis for estimating value. Market-based approaches consider known pricing metrics for comparable assets as direct evidence—or at least as a reasonable proxy—of value for the subject asset. Income-based approaches consider an expected benefit stream, typically measured in cash flow, discounted or capitalized to obtain a present value as of a certain date.

Simply put, income-based value calculations consider three key variables: (i) an expected cash benefit; (ii) a discount rate; and (iii) a time variable. Many of us first encountered this combination of variables in the following formula which is used to calculate compound growth in finance and other fields:

FV = PV x (1 + r)n

Where:

FV = Future Value

PV = Present Value

r = rate of growth per period

n = number of compounding periods.

Rearranging the above terms with some basic algebra, we obtain a formula which allows us to calculate a present value. The formula that results is the fundamental basis of discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis:

PV = FV / (1 + r)n

While the above formulas are based on calculations for a discrete period (n), we may also calculate a present value for a benefit stream assumed to continue forever, known as a perpetuity. The present value of a perpetuity can be calculated using the Gordon Growth Model, which can be stated as:2

PV = FV / (r – g)

The Gordon Growth Model introduces a growth variable (g) which is subtracted from the discount rate. This growth variable represents the amount of growth expected in the benefit stream per period. The combined term “r-g” is referred to as the capitalization or “cap” rate. To illustrate, assume the discount rate (r) is determined to be 20% and that long-run growth (g) of 3% is expected. Under this set of assumptions, the cap rate would be 17% (.20 - .03 = .17).

Capitalization is used extensively in valuing real estate where annual rental income is divided by a cap rate as a means of deriving an indication of value for the subject property. Cap rates—along with certain types of mathematically-related capitalization multiples considered later—address issues of risk and growth in a combined manner.

III. Uncertainty and Risk

Uncertainty is an objective feature of the universe. It is a fact of the world in which we live. In contrast, risk is based on perception. It is our perception of uncertainty and potential outcomes that gives rise to risk and our responses to it.3

While the discount rate may be the most apparent place to reflect risk in a present value calculation, it is not the only place. In an income-based analysis, uncertainty and risk can be considered through the following:

- Discount Rate (r)—risk and return expectations can be reflected through discount rates.

- Future Value (FV)—forecasted values can be adjusted directly to reflect realization risk—the risk that forecasted results will fall short. Adjustments may occur by simply reducing projected values or by applying probability factors as a basis for reductions.

- Time (n)—the time variable can be adjusted to reflect risk associated with longer realization periods.

- Multiple Scenarios—outcome uncertainty can be reflected through the use of differing scenarios which may be probability-weighted and summed to obtain a single value.

- Variable Ranges—uncertain input variables such as units sold or price can be considered in ranges and used in different combinations. This is a basic feature of Monte Carlo simulation which allows for the consideration of input variable ranges which lead to ranges of potential outcome values.

IV. Cost of Capital Basics

While we generally think of costs being expressed in terms of dollars, euros or some other currency, the cost of capital is generally expressed as a percentage over time. Consider the annual percentage rate (APR) for a credit card. If a credit card has a 12 percent APR, the cost of capital to the cardholder is 12 percent a year or 1 percent per month. In the formulas presented previously, the “r” variable represents this cost.

The cost of capital is forward looking because it is based on an investor’s expectations, specifically the investor’s return expectation which provides the applicable discount rate used in calculating a present value. The concept of a “present value” is based on the idea that having a dollar today is worth more than the possibility of receiving a dollar tomorrow, due to the potential reduction in future purchasing power resulting from inflation coupled with the risk of not receiving the dollar later. Restating this more technically, the cost of capital includes two basic components:4

• A Risk-Free Rate represents a rental rate for capital that includes expectations for inflation and rate variability over time (i.e., term risk) but not default risk. U.S. government treasury securities— t-bills or t-bonds as they are known in the United States—provide a generally accepted basis for riskfree rates due to the lack of risk related to payment default by the U.S. government.5 Discount rates used for valuation purposes are generally stated in nominal terms because they include this risk-free component, thus reflecting expected inflation. For proper matching, cash flows being discounted with nominal rates should also reflect expected inflation.6

• A Risk Premium reflects the possibility that the amount and timing of benefits will fall short of estimates. This component considers what is referred to as “default risk” in the context of debt-related payments that may not occur when expected or in the amount expected. Herein, I use the term “realization risk” to more broadly address the notion of not realizing forecasted cash flows when or in the amount estimated.

When performing a DCF analysis, a discount rate should be selected that reflects a rate of return commensurate with the risk of obtaining estimated future cash flows. To illustrate this point, consider a Fortune 500 company making a $10 million investment in a high tech start-up, ABC Systems. The Fortune 500 company is able to borrow funds at 5 percent and has an overall cost of capital of 9 percent. Based on due diligence and experience with similar businesses, the venture capital firm that will also be investing $10 million in ABC Systems expects to receive a 40 percent annualized return on this deal.

If the Fortune 500 company borrows $10 million to make this investment, what discount rate should it use in its analysis of this investment? While its cost of borrowing is only 5 percent and its overall cost of capital is 9 percent, the appropriate cost of capital for the ABC Systems investment is 40 percent because this represents a market-based return expectation for an investment of this type. The fact that the Fortune 500 company is able to borrow the funds it invests at a much lower rate is a reflection of the risk ascribed to the Fortune 500 company as a borrower which does not alter the higher risk of an equity investment in ABC Systems that dictates a 40 percent discount rate.

The cost of capital is driven by the nature of the investment not the source of the funds being invested. However, as will be discussed further below, capital providers such as private equity groups and venture capital firms tend to make certain types of investments that reflect certain levels of risk. Understanding the return expectations for such investors can be helpful in assessing the cost of capital for private companies, capital investment projects and IP-related assets.

V. Returns On Capital and Assets

When trying to understand discount rates for IP, the logical place to start is discount rates for businesses. Business capital takes two basic forms: debt and equity. Businesses deploy capital to purchase assets and pay expenses in an effort to generate revenues and profits. This section considers the way required returns for debt capital, equity capital and various assets interact to help inform the way discount rates for IP should be assessed.

Debt capital is provided by bond investors, banks, and others that lend money with the expectation that they will be paid back with interest. In discussing risk premiums earlier, the notion of “default risk”—the risk that a debtor will not make payments when or in the amount expected—was introduced. To protect themselves from default risk, many lenders secure their interests by collateralizing assets and/or requiring personal guarantees from business owners. In contrast, unsecured lenders lack collateral and often face greater downside risks. In the event that a business fails and must liquidate its assets, senior secured creditors get their money first with unsecured creditors getting paid next, assuming sufficient proceeds. If there’s anything left after paying creditors, it goes to equity holders where additional liquidation preferences may exist between those holding preferred and common equity.

Equity capital can be obtained from direct investments by owners and through the generation of profits that remain in the business as retained earnings. Bankers sometimes refer to equity as “risk capital” because, unlike debt that is to be repaid according to certain terms, equity capital providers generally make their money when the business generates profits and positive cash flow after others have been paid. Again, equity holders get what’s left over, which may not be anything.7

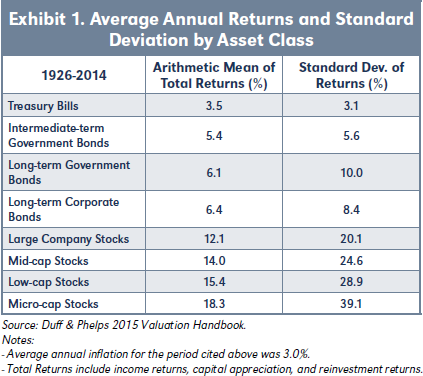

Intuitively, we understand that equity capital is generally riskier than debt capital and thus commands a greater level of return to compensate for this risk. The data presented below in Exhibit 1 helps to confirm this intuition:8

As we move from the top of Exhibit 1 to the bottom, we see that mean returns and variability increase. Logically, risk-free government securities offer the lowest returns and variability. Slightly riskier corporate debt comes next. Then we observe four classes of public equity from large company to micro-cap where the predictable march of risk and return continues with the smallest companies providing the greatest return opportunity and the greatest risk.

Returns on Capital

While some businesses are capitalized with all debt or all equity, many businesses utilize both. To assess the cost of capital for a business with a mixed capital structure, we need to understand the relative costs and proportions of debt and equity. Consider these examples:

1. The high tech start-up discussed earlier, ABC Systems, which was being funded with $20 million in equity. Since the business did not obtain interestbearing debt for funding, then its cost of capital is 40 percent, the market-based return expectation for equity capital in this business.

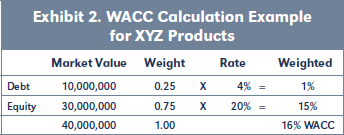

2. A stable manufacturing business, XYZ Products, with $10 million in debt financing at 4 percent interest (net of tax benefits) and $30 million in equity (at market value) with a 20 percent cost of equity.

For XYZ Products, we see that debt represents 25 percent of the capital structure while equity represents 75 percent. Applying these weights to the respective costs associated with debt and equity capital, we are able to calculate the company’s weighted average cost of capital (“WACC”) as indicated in Exhibit 2:

The WACC calculated above represents XYZ Products’ overall cost of capital.9 Put another way, it represents the overall level of risk and return associated with realizing all future cash flows of the business.10

A company’s WACC is often used as a basis for what is referred to as a “hurdle rate,” a discount rate used for capital budgeting purposes. This rate is used in discounted cash flow analysis to demonstrate how proposed investment projects may or may not provide returns at or above a level that clears the required “hurdle” set by management. The basic idea is that a capital investment should at least earn back the amount invested plus the cost the company pays for the use of its capital, and if it can’t, then the project should be rejected. While certain investment projects may indeed reflect risk and return characteristics comparable to those of the company overall, others will not. Hurdle rates are often misused when applied universally as a one-size-fits-all discount rate. Capital investment projects reflect varying levels of risk, often above that of the hurdle rate, particularly when dealing with projects involving technology and IP.

Returns on Assets

Continuing with the example from Exhibit 2, if the capital of XYZ Products is to generate a 16 percent overall return, the assets of the business as a whole —including IP and other intangibles—must also generate a 16 percent overall return. This is true because of the most basic premise of accounting that assets equal liabilities plus equity (A = L + E). This premise is demonstrated by the fact that a balance sheet must “balance.” Thus, if we expect a 16 percent return on one side of the balance sheet, we should expect a 16 percent return from the other side too. This concept applies to the economic view of the business in which the balance sheet is recast based on the notion of economic or market value.11

In Exhibit 2, we see that the overall 16 percent return on capital (the WACC) decomposes into two components: debt at 4 percent and equity at 20 percent. Since the return on capital must equal the return on assets, it makes sense that the 16 percent return on assets can also be decomposed into its constituent parts based on asset types that demonstrate varying degrees of monetization risk.

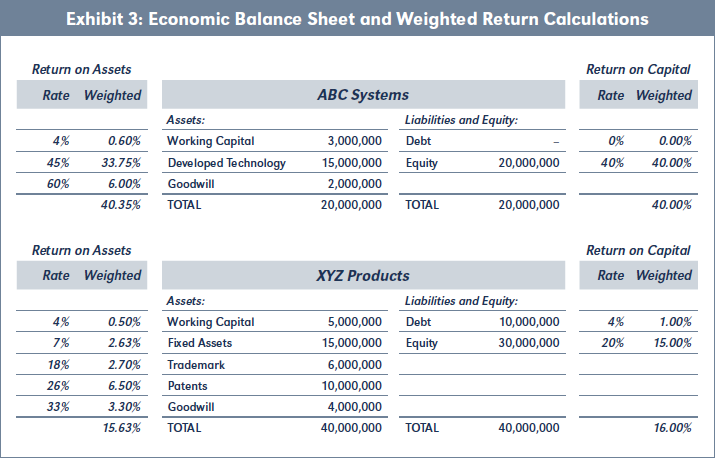

Exhibit 3 presents a highly summarized economic balance sheet for the two hypothetical companies being considered herein along with return-related information for illustration purposes.12

Looking at the left-hand side of the economic balance sheets we note that assets become more risky and illiquid as we move from top to bottom. On the right-hand side, we note that capital accounts begin with interestbearing debt and end with “risk capital” or equity. These characteristics hold true for accounting-based balance sheets, too. Given that risk increases as we move from the top to bottom, it makes sense that rates of return must also increase. But on a weighted average basis, each side must be roughly equivalent.13

Exhibit 3 provides evidence that XYZ Products is a more established and less risky business than ABC Systems, given the availability of inexpensive debt and its lower cost of equity. Likewise, the intangible assets of XYZ Products require lower rates of return than those of ABC Systems because they have been “de-risked” over time by XYZ Products as part of its established business.

Businesses are portfolios of assets that work together to create returns. Assets and business activities that provide sufficient value tend to be retained, while those that don’t tend to be eliminated over time. Additionally, to the extent that a portfolio of assets serves and includes various customers, products, technologies and employees, benefits of portfolio diversification can exist and serve to further reduce risk and/or increase returns. For these reasons, XYZ Products benefits from its assets being time-tested and diversified as compared to those of ABC Systems which are relatively unproven and riskier.14

Since an economic balance sheet is based on economic value as of a stated date, not historical cost, we see an entry for goodwill as the last asset in Exhibit 3 to account for the final component of intangible value that cannot be specifically identified. This illustrates the type of analysis that occurs in a purchase price allocation when one company buys another and must place the newly acquired assets on its balance sheet at “fair value” based on the price paid.15 While economic balance sheets are based on value at a stated point in time, accounting balance sheets are based on historical cost. However, these two worlds come together in a business acquisition setting where the buyer’s cost is based on the purchase price and economic value of acquired assets.

This section demonstrates how returns on IP assets (and other assets) can be considered in the broader context of a business and how returns on assets compare to and reconcile with returns on capital. This section also illustrates how IP within the context of an established business with a track record for effectively using the IP can lead to less risk and reduced return requirements as compared to the same IP in the context of a new venture or on a stand-alone basis.

With going-concern businesses, we typically see that the WACC provides a floor value for returns on IP assets, but that returns for IP and other intangibles are often at or above the cost of equity.16

VI. IP Monetization Approaches and Risks

IP value and risk is contextual. Differing uses of IP may present differing levels of monetization risk as relevant to the determination of a discount rate.

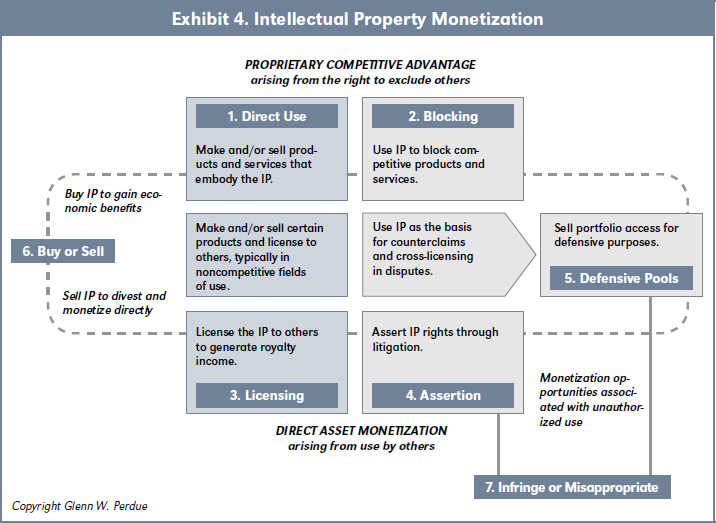

As an owner, assignor, assignee, licensor, licensee, or infringer, IP monetization and related risks are viewed in different ways. Exhibit 4 summarizes typical ways IP is monetized. While this exhibit is intended to address the topic of monetization broadly, it applies most directly to patents, particularly as related to defensive uses that involve the right to exclude, blocking, and counterclaims. Notwithstanding these nuances, this general framework provides a helpful economic backdrop for discussion related to all types of IP.

As indicated in Exhibit 4, IP can be monetized directly or indirectly. Indirect monetization through direct use and blocking is generally pursued with the intent of capitalizing upon sources of proprietary competitive advantage enabled by the IP that lead to greater revenues and profits. In contrast, direct asset monetization is pursued in an attempt to obtain payments from IP users by selling, licensing or asserting the IP. Since direct asset monetization relies upon IP use and payment by others, monetization risks associated with royalty reporting, litigation and collection are introduced that don’t exist with direct use or blocking where no external payment is required.

1. Direct Use

Direct use occurs when owned IP is embodied in a company’s products or services with the hope of selling more units, selling at higher prices, and/or enjoying lower costs than would have occurred without the IP.

When valuing an established business, value is often assessed under the premise of a going concern and the assumption that business cash flows will continue in a manner consistent with past performance. Logically, cash flows and value ascribed to IP embodied in established products and services reflect common business risks. In this setting, IP risk is tightly coupled with overall business risk.

But IP may also be new and part of a planned offering being developed with the hope of penetrating a new or existing market. In this setting, whether the business using the IP is established or not, unknowns associated with development costs, commercialization challenges, regulatory approval, competition, market acceptance and other factors may present risks consistent with those encountered by venture capital firms that invest in early-stage ventures.

Contrasting the above examples, we see less IP monetization risks in the established business setting than in the setting of a new product or venture. Discount rates should reflect these differences. IP-related discount rates in the established business/product setting might reasonably be at or around the company’s cost of equity while an early-stage venture capital rate might be more applicable to the IP being deployed in the setting of a new product or new venture.

2. Blocking

Economic value through blocking is created by preventing competitive entry or causing a competitor to exit the market.

The benefits of blocking may apply to existing products and services that embody the blocking IP or other offerings that don’t. If existing offerings embody the IP, blocking can limit competition and, accordingly, may allow for higher prices and greater market share. In this setting, where both internal use and blocking occur simultaneously, the monopoly value of the IP is demonstrated. If the IP is not embodied in existing offerings, it may be used to prevent competitive entry considered threatening to existing offerings—such as profitable incumbent technology with dominant market share that could be rendered obsolete by new technology that embodies the blocking IP. In this setting, the blocking IP insulates legacy products from competition.

Under the premise that blocking value arises from the preservation of existing cash flows, the discount rate may be properly based on the cost of capital for the company overall or the legacy business segment specifically.

3. Licensing

A licensee faces the same types of risks that occur under internal use, thus leading to similar risk considerations. If a licensee is non-exclusive, it may face additional competitive risk from others in the market using the same IP. This risk may have been reflected in the royalty rate, but may also be reflected in estimated future cash flows and/or the discount rate.

With IP that has generated historic royalties and is expected to continue doing so, the riskiness of the activity that underlies these royalty payments—such as the sale of products that embody the licensed IP—is a primary risk driver for both licensee and licensor. However, additional risks associated with royalty reporting, disputes and collection can exist that may justify higher discount rates for the licensor.

To demonstrate this last point, consider a multinational licensing arrangement where licensees in different countries have various sub-licensees. More realization and collection risk may exist among certain licensees than others due to economic, cultural and political factors that differ across countries. Varying business risks and enforcement challenges may also exist. In this setting, it may be appropriate to use different discount rates in discounting expected cash flows from differing sources.17

4. Assertion

Under an assertion-driven business model, the ability to monetize IP is based on a variety of factors which may include the strength of the IP rights and the utility of the IP in its unauthorized use. To the extent that an assertion action could go to trial, IP strength and utility factors become relevant to the issue of damages and likelihood of recovery.

With asserted patents, we encounter three discrete legal factors that influence value: validity, enforceability, and infringement. Each may have their own relevant probability. In addition, appeal and recovery trends should also be a consideration.

While non-practicing entities may only recover economic damages through a reasonable royalty in patent cases, practicing entities may be able to recover damages through a reasonable royalty or lost profits.18 Since 2000, approximately 80 percent of patent cases with damage awards have included an award of reasonable royalties, while only 30-40 percent included an award of lost profits. Additionally, around 70 percent of district court decisions get appealed to the Federal Circuit.19

In assessing the assertion value of a patent or other IP, factors related to the time, expense, and probability of recovery should be considered in assessing value and the cost of capital associated with funding the assertion effort. Specialized litigation finance firms exist to fund litigation projects. Recovery fees charged by these firms—net of the market value for professional services provided under the arrangement—would provide direct market-based evidence for the cost of capital related to an assertion effort.20

5. Defensive Pools

Defensive pools are a relatively new form of patent monetization by which companies pay to gain access to patents which they can use as the basis of counterclaims in assertion actions brought against them. Companies such as RPX and Intellectual Ventures make their patent arsenals available to customers for this purpose.21 The success of this business model is based on the ability to acquire patents considered helpful in defending against assertion actions while pricing access in a manner that makes economic sense for customers and provides sufficient returns to the provider.

In acquiring new patents, the pool provider might reasonably use its existing WACC as the basis for discounting related cash flows. However, risk premiums may be appropriate due to expected legislative changes, forthcoming judicial opinions, uncertainty associated with a new technological area, or weaknesses associated with specific patents under consideration (see the Alice discussion below).

6. Buy or Sell

A buyer of IP may make a purchase with the intent of monetizing the IP using one or more of the approaches noted thus far. Such a purchase could range from a single piece of IP for a very specific purpose or a portfolio of IP underpinning an entire business. With the purchase of a single piece of IP, the selection of an appropriate discount rate would be influenced by the anticipated means of monetization. With the purchase of a large IP portfolio, the discount rate might be more appropriately considered within the broader context of the overall business relative to other assets acquired.

A seller may want to consider the value of the IP based on their current use and also estimate the value of the IP to a prospective buyer as a means of calculating a potential range of negotiation for the sale. This analysis could involve any or all of the monetization approaches and discount rate considerations noted thus far.

7. Infringe or Misappropriate

Finally, IP can be monetized through infringement or misappropriation. While some IP users may be unaware of their wrongful use, others use IP with some knowledge that their use may be considered wrongful. Once an IP user becomes aware of its potentially wrongful use, it is faced with the decision of whether or not to continue using the IP. If the decision is made to continue, then the future benefits of use may be considered relative to potential costs associated with legal fees and damages on a probability-adjusted basis.

Teva Pharmaceuticals is a company that makes rational business decisions to risk infringement. Teva has launched generic drugs “at risk” after filing a Paragraph IV certification under the Hatch-Waxman act indicating that they consider patents of a branded drug producer to be invalid, unenforceable, or not infringed. Based on this filing and having obtained necessary FDA approvals, Teva has launched products before the issue of infringement has been settled by the court.

Financial analysis in this setting may involve probability adjusted scenarios that consider the cost and likelihood of an infringement finding in court versus the benefits associated with continued royalty-free use. In this setting, the analyst should consider risk in the discount rate that is not already considered in probability adjustments.

Monetization Approaches Based on Unauthorized Use

In Exhibit 4, the monetization approaches associated with Infringement and Misappropriation (7), Assertion (4), and Defensive Pools (5) are specifically identified as a sub-group because they share common vulnerabilities and risks.

On June 19, 2014 the Supreme Court issued its unanimous decision in Alice Corp. v. CLS Bank International. In Alice, the Supreme Court considered the issue of patentable subject matter by specifically weighing in on software patents. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision to invalidate the patents at issue, Alice has been applied by district courts and the USPTO to invalidate many other software-related patents. The decision in Alice along with changes at the USPTO allowing new post-issuance validity challenges are but two examples of increased patent monetization risks that will impact probability adjustments and discount rates used in patent valuations.

The cumulative economic impact of various legislative, regulatory and judicial actions, many of which targeted non-practicing entities, was being felt by the end of 2014. Patent wars involving Apple, Samsung, Google and other big players were also cooling down during this period. As a result, some businesses based upon unauthorized patent use lost value. For instance, between early July 2014 and year-end, RPX lost 30 percent of its market value. This slide in value occurred shortly after the Alice decision.

Risks such as those created by Alice and other changes in the market can be reflected through decreases in forecasted revenue, increases in costs, reduced success probabilities or increased discount rates in financial modeling.

VII. Part One Conclusion

This concludes Part 1 of this two-part paper. Part 2, which follows in this issue, will begin with Section IX—Discount Rate Sources, Signposts and Calculation Methods. In addition, Part 2 will also contrast differences in IP-related discount rates, capitalization rates and calculation methods that can occur with differing types of IP.

- Harvard Business Review OnPoint—Summer 2014, see “Decisions and Desire” by Gardiner Morse.

- To assist the reader, I have used consistent variable names. Some presentations of present value, future value and the Gordon Growth Model use different variable names.

- The Flaw of Averages by Dr. Sam L. Savage, copyright 2009. See Chapter 7.

- Cost of Capital: Applications and Examples (5th Edition) by Shannon P. Pratt and Roger J. Grabowski, page 6.

- Some argue that t-bills and other forms of U.S. government debt have some default risk, particularly as U.S. debt levels rise as a percentage of GDP. Notwithstanding this argument, t-bills are generally considered to be the best available proxy for a risk-free rate in assessing discount rates. Additionally, many argue that risk-free rates have been artificially low in the after-math of the great recession due to Fed policy that kept rates artificially low when considered in the context of historical rates that reflect less intervention by the Fed.

- Cost of Capital: Applications and Examples (5th Edition) by Shannon P. Pratt and Roger J. Grabowski, page 7. While discount rates are typically stated in “nominal” terms, for certain purposes they may be stated in “real” terms by explicitly not including inflation. For instance, if forecasts are stated in current dollars (i.e., they don’t reflect increases due to inflation) it is appropriate to subtract expected inflation from the discount rate, thus restating it in real terms.

- There are differing types of equity, including preferred equity which may act like debt in that a regular dividend is promised with a potential bal- loon payment at some point. However, a discussion of differing types of equity securities is beyond the scope of this article.

- 2015 Valuation Handbook: Guide to Cost of Capital published by Duff and Phelps, see Exhibit 2.3.

- Obtaining the market value of equity for a private company is considered further in Part 2 of this article, but involves some business valuation concepts and techniques that are beyond the scope of this article.

- While the focus of this article is on the cost of capital for business, governmental entities also have a cost of capital. Yields on government bonds at the federal, state or local level may be relevant considerations in valuing IP use that involves governmental entities. The cost of capital for private sector peers, such as for-profit hospital or prison operators, might also be a relevant consideration in assessing the risk of a govern- ment enterprise.

- Accounting based balance sheets are based largely on the notion of historical costs, not economic value.

- In the type of analysis illustrated in Exhibit 3, “Work- ing Capital” is presented on net, debt-free basis while “Debt” represents all interest-bearing debt, which does not include trade payables, as this is included in Working Capital. Other types of intangible assets, such as those that arise from customer relationships and contracts, are not reflected in these examples for the sake of brevity. A full discussion of the concepts considered in this section and this footnote is beyond the scope of this article.

- As a matter of general practice, the WACC is determined first then the rates for assets are determined, such that they equate roughly on a weighted average basis. It is not neces- sary for these values to equate exactly as illustrated in these examples.

- Harry Markowitz won the Nobel Prize in 1990 for his contribution to the field of financial economics based on the development of his theories related to Modern Portfolio Theory, which considers the manner in which properly diversifying investment portfolios can reduce overall portfolio risk. While Markowitz considered these concepts from the perspective of inves- tors in stocks and bonds, these concepts apply more broadly as considered here.

- ASC 805 (Business Combinations) and ASC 820 (Fair Value Measurements and Disclosure) as promulgated by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) provide further information on these Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

- IP-centric businesses, such as music publishing companies, film studios, and biotech companies, can provide an exception to this general rule if their primary assets are a mixed portfolio of low-risk and high-risk IP. In this setting, low-risk IP may be deemed to have a cost of capital at or below the WACC.

- Costs of Capital—You Can Love More Than Just One by David Wanetick, les Nouvelles June 2013.

- 35 U.S. Code § 284—Damages.

- 2014 Patent Litigation Study by PwC (July 2014).

- Litigation finance is a small but growing area of specialty finance and a full discussion of this topic is beyond the scope of this article. Another proxy for the cost of capital is the dif- ference between the cash and contingent fee prices charged by legal counsel. This difference represents the risk premium associated with the litigation effort.

- Based upon correspondence with Cory Van Arsdale, Senior Vice President of Global Licensing at Intellectual Ventures (“IV”), I understand that IV sells patents to buyers for defensive purposes but that its business also involves licensing unrelated to disputes along with the creation of new IP and the development of business- es around IP through joint ventures, spin-outs and other means. In this respect, IV considers itself an “Invention Marketplace” in which defensive IP sales are merely one aspect of the business.