les Nouvelles June 2020 Article of the Month:

Trademarks, Brands And Goodwill: Overlapping Sources of Economic Value

Kraft Analytics, LLC

Managing Member

Nashville, TN, USA

Businesses develop and acquire assets that are used to generate revenues and profits. These assets may be financial, tangible or intangible in nature. Collectively, these assets—and their profit generating potential—form the basis of business value. Financial assets such as cash and receivables are distinct and easy to understand. So, too, are tangible assets such as real estate and equipment. In contrast, intangible assets may not be identified on financial statements and often deal with more elusive concepts such as legal rights, proprietary technology and relationships. There is great consensus in the worlds of marketing, economics and accounting that intangible assets associated with trademarks, brands and goodwill create value— value that arises from market awareness, relationships with customers and a good reputation. This article explores these sources of value.

Accounting vs. Economic Value

Financial statements based on generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) reflect the value of assets based on the principle of "lower of cost or market" in keeping with the underlying principle of conservatism. Put simply, accounting-based asset values should reflect the lower of the historical cost (less adjustments for depreciation, amortization, etc.) or market value so that the financial statements don't overstate asset values.

In contrast, economic value is based on the concept of what another party would pay for an asset. Stock market data reflects economic value because it is based on prices paid in an open market. Stock prices often have little to do with a company's accounting-based balance sheet. After all, investors are generally more concerned with expected earnings and growth. However, when one business buys another, accounting and economic views of value converge because the buyer will place acquired assets on its balance sheet at "fair value," a market-based value.1 Due to this requirement, intangible assets that may have never been reflected on the seller's balance sheet are indicated on the buyer's balance sheet in a manner that reflects economic value.

Five generally-recognized categories of intangible assets are (i) marketing-related; (ii) customer-related; (iii) artistic-related; (iv) contract-related; and (v) technology- based. Some groups of acquired intangibles may also be referred to as "brand intangibles."2 Exhibit 1 graphically presents a purchase price allocation for a hypothetical technology company that generated revenues of $5 million and earnings before interest taxes depreciation and amortization ("EBITDA") of $1 million in the prior year. In this example, the buyer purchased the assets of the business for $15 million which equates to 3 times revenue and 15 times EBITDA.3

The accounting-based balance sheet of the company in Exhibit 1 is depicted in dark blue and reflects asset values of $4 million for cash, accounts receivable, a building and other assets. On the other side of the balance are liabilities totaling $1 million and equity totaling $3 million. However, based on the $15 million sale price, company equity is valued at $14 million—4.7 times the accounting-based value for equity. The reason: intangible assets which cause the economic value associated with expected income to exceed accounting- based value.4

Consistent with Exhibit 1, for many businesses, economic value beyond what is reflected on the balance sheet can be largely attributed to the value of a good name in the market and strong customer relationships.

Trademarks and Brands

Black's Law Dictionary provides the following definitions, explanatory narrative and case law support for "trademarks" and "brands":

Trademark—A word, phrase, logo or other graphic symbol used by a manufacturer or seller to distinguish its product or products from those of others. The main purpose of a trademark is to designate the source of goods or services. In effect, the trademark is the commercial substitute for one's signature.

The protection of trademarks is the law's recognition of the psychological function of symbols. If it is true that we live by symbols, it is no less true that we purchase goods by them. A trademark is a merchandising short-cut which induces a purchaser to select what he wants, or what he has been led to believe he wants. The owner of a mark exploits this human propensity by making every effort to impregnate the atmosphere of the market with the drawing power of a congenial symbol.Whatever the means employed, the aim is the same—to convey through the mark in the minds of potential customers,the desirability of the commodity upon which it appears. Once this is attained, the trademark owner has something of value. If another poaches upon the commercial magnetism of the symbol he has created,the owner can obtain legal redress. Mishawaka Rubber& Woolen Mfg. Co. v. S.S. Kresge Co. 316 U.S. 203,205, 62 S. Ct. 1022, 1024 (1942)

Brand—A name or symbol used by a seller or manufacturer to identify goods or services and to distinguish them from competitor's goods or services; the term used colloquially in business and industry to refer to a corporate or product name, a business image, or a mark, regardless of whether it may legally qualify as a trademark. Branding is an ancient practice, evidenced by individual names and marks found on bricks,pots, etc. In the Middle Ages, guilds granted their members the right to use a guild-identifying symbol as a mark of quality and for legal protection.

As illustrated above and discussed further below, the term "brand" can be used broadly or narrowly. In the narrowest and most colloquial sense, it is a synonym for "trademark." In its broadest sense, "brand" encompasses other intangibles, including goodwill.

Enterprise and Personal Goodwill

In discussing the notion of goodwill, let's begin with a common definition from the Miriam Webster Dictionary:

Goodwill—The favor or advantage that a business has acquired especially through its brands and its good reputation.

This definition underscores key concepts associated with economic "advantage" arising from "brands" and a "good reputation." The definition that follows from Black's Law Dictionary also references "reputation" and ties in the concept of "patronage" which most obviously relates to customers but could also include investors and others that support the business.

Goodwill—A business's reputation, patronage,and other intangible assets that are considered when appraising the business, esp. for purchase; the ability to earn income in excess of the income that would be expected from the business viewed as a mere collection of assets.5

The final definition provided below from the International Glossary of Business Valuation also references "reputation" in addition to referencing "name" and "customer loyalty." In considering these factors and "similar factors not separately identified" this definition underscores how goodwill represents intertwined benefits associated with marketing and customer relationships.6

Goodwill—that intangible asset arising as a result of name, reputation, customer loyalty, location, products,and similar factors not separately identified.

Just as "brand" can be a broadly encompassing term that includes trademarks, the term "goodwill" can be similarly broad. In the above definitions, we see that these terms can reference one another and overlapping concepts such as name, image and reputation.

Unlike trademarks, which create value that is inextricably tied to the business, goodwill may be tied to the business as "enterprise goodwill" and/or certain individuals within the business as "personal goodwill." In discussing the definition of goodwill and distinctions between its personal and enterprise forms, Dr. Shannon Pratt states:

First, we should understand the classic definition of goodwill is the propensity of the customer to return tothe business. Having said that, the separation of personal versus enterprise goodwill depends on whether(or the extent to which) the customer returns because of the individual or elements that belong to the enterprise.

7

In Personal Goodwill in Search of a Functional Definition, David Wood defines personal and enterprise goodwill as follows:

Personal goodwill is the value of earnings or cash flow attributable to attributes of the individual that results in earnings from customers that return because of the individual, in earnings from new customers who seek out the individual, and in earnings from referrals made to the individual.

Enterprise goodwill is the value of earnings or cash flow directly attributable to attributes of the enterprise that result in earnings from customers that return because of the enterprise, in earnings from new customers who seek out the enterprise, and in earnings from referrals made to the enterprise.8

In 1998, the United States Tax Court recognized the existence of personal goodwill as relevant to the tax treatment of gains realized from business transactions in the Martin Ice Cream matter. In this case, a company owner with personal relationships developed prior to forming the company distributed Haagen-Dazs ice cream to various grocery chains based purely on handshake deals (i.e., no written contracts). The tax court ruled that the "seller's rights" conveyed in the sale belonged to the owner, not the corporation. As a result, capital gains treatment was appropriate for the gain realized in the sale of this personal asset.9

In situations where businesses are being sold and a high degree of personal goodwill is present, buyers may require employment or consulting agreements with non-compete/non-solicitation provisions that allow the buyer to retain personal goodwill from key individuals once it has been conveyed. In situations where non-compete/non-solicitation agreements are in place with key individuals before a sale, these individuals have effectively transferred some portion of their personal goodwill to the business which may then be assigned to the buyer contractually.

States have various restrictions on doctors and lawyers engaging in non-compete agreements to protect patients and clients that rely on their counsel. With these professionals and others, a high degree of personal goodwill exists due to reputation, education and expertise—sources of value that follow the professional. The trust-based nature of professional relationships contributes further to personal goodwill. While your personal physician may be part of a medical group, if he or she leaves that group but stays in the area, chances are you will follow. This is personal goodwill at work.

Personal goodwill may also exist with business owners and sales people that have developed strong relationships with customers. Consider the long-time owner of a local automotive dealership that bears his name. The dealership is a beneficiary of value arising from the owner's personal goodwill. Similar situations exist with insurance brokers and others that have developed a book of business over many years with loyal customers.

In contrast, when we deal with Amazon by making on-line purchases, our interaction and any resulting goodwill accrues to the enterprise. A similar situation exists when we buy a Coca-Cola or an Apple iPhone.

Brands and Brand Equity10

What constitutes a "brand" may differ depending on whether it's being viewed from the perspective of accounting, economics, management or marketing.11 Even within these disciplines, brands may be viewed narrowly or broadly. In the narrowest sense, a brand is the sum of elements that constitute the visual identity of a company—the name, logo, colors, and shapes associated with a business or product. A broader view of the notion of brand includes not only these visual elements but also related market associations. This more expansive view reflects the manner in which a brand embodies the image and reputation of the seller and may also consider associations with other stakeholders such as employees, investors, suppliers, distributors, and regulators.12 Clearly, if a strong brand helps a company attract talented employees, investors or desirable resellers, this too provides economic value.

While the narrower view of brand would consist of marketing-related intangible assets such as trademarks, service marks, and trade dress (unique color, shape, package design, etc.), the more expansive view of brand may reflect goodwill and value from other intangible assets.

Brands help businesses by:

- Driving demand for products and services due to brand awareness and desirability;

- Providing a unique means to identify the company and its offerings;

- Helping the company communicate its quality and differentiating characteristics;

- Enabling messaging efficiency in advertising, public relations, on-line and word-of-mouth;

- Providing a platform for the introduction of new products and services that inherit the market benefits of the brand; and

- Allowing for price premiums and better profits to the extent that a company's brand is associated with a higher degree of quality or desirability than competitive offerings.

Regarding this last point, the pharmaceutical industry understands the power of brands as a means of generating price premiums.

When branded pharmaceutical products lose patent protection, approved generic drugs are allowed to enter the market. Faced with losses from cheaper products that are perfect substitutes13 one might consider it reasonable for the branded manufacturer to reduce price in an effort to maintain production volumes and market share. What actually occurs is often quite different. Manufacturers often raise the price of their branded drug following generic entry because a brand-loyal segment of customers is willing to pay more due to the perceived quality of the branded product over generic alternatives. With successful pharmaceutical products, as the value of patent protection wanes over time the value of the brand often strengthens.

Brands create economic value for businesses, which may be referred to as "brand equity." One view suggests that brand equity is derived from a combination of (i) perceived quality; (ii) brand loyalty; and (iii) brand awareness and associations that exist in the relevant market.14

Based on the sources of value noted above, business investments in the following can logically contribute to brand equity:

Marketing and Legal:

- Trademark registration.

- Brand identity development through name selection, visual design, and related research through focus groups and other sources.

- Marketing strategy to assess market-positioning, brand messaging, pricing, etc.

- Advertising, public relations, and promotional activities that create brand awareness and communicate brand attributes.

- Brand enforcement to insure compliance with brand usage policies within the company and to prevent

- Investments that differentiate the company and its offerings.

Direct and Indirect Sales:

- Direct sales force investments (e.g., selection, education/ training, etc.).

- Indirect channel investments in resellers of the company's products and services.

- On-line sales investments.

Development and Support:

- Product development activities that perpetuate the brand.

- Employee training and development activity that supports the brand (e.g., tech support, customer service).

- On-line support investments.

- Packaging that reinforces the brand.

- Quality control activities that reinforce the perceived quality of the brand.

All of the items listed above in some way contribute to the image, reputation, and awareness of the company and its offerings. In this regard, each of these items constitutes a brand-building investment even though some may not fit neatly within the classical rubric of marketing. For instance, product development might be deemed more of an engineering function in some companies. However, at a company like Apple, product development reinforces a brand identity built on developing fashionable, leading-edge consumer products like the iPad and iPhone. In the fashion industry, ties between product development and the brand are particularly apparent with logo treatments, color palettes, patterns and other design elements that are associated with the brand.

Apple also provides a great example of how front-line employees can contribute to the goodwill of the company. Most people I know (including myself) that have visited the genius bar at an Apple store come away feeling impressed and satisfied with the service they receive. While those providing this service are typically smart and personable, the value of this service accrues to Apple's enterprise goodwill because these interactions generally cause us to be more loyal to Apple, not the individual providing the service. After all, if that individual left Apple to join Samsung, I doubt many of us would ditch our iPhone to start using a Samsung Galaxy phone, despite how smart and personable they may be. This lies in contrast to the earlier example of a physician leaving their current medical practice. In that case, loyalty— and thus revenue—generally follows the doctor, not the company.

I recently had lunch at a Chick-fil-A restaurant. While eating, I overheard an interview at an adjacent table. The interviewer was explaining the service philosophy and values of Chick-fil-A to a job candidate with great clarity and conviction. I have always been impressed with the food quality, value, and customer service at Chick-fil-A and overhearing this interview amplified these positive sentiments. But much like the brilliant folks at the Apple genius bar, my heightened loyalty attaches to Chick-fil-A, not the dedicated interviewer because if she left to work at another nearby restaurant, this would not influence my lunch choice for the day.

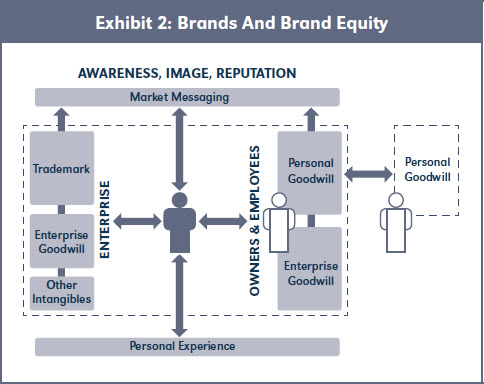

Exhibit 2 illustrates components of brands and brand equity discussed thus far. At the center of the model is the individual stakeholder interacting with the business which is considered to be a customer for the sake of this discussion.

Market Messaging related to the brand may be provided through traditional media (print, broadcast, point-of-purchase, etc.), on-line media, at shows/ events and through word-of-mouth. Messaging also occurs through others that visibly support a certain brand through the cars they drive, the clothes they wear and other such displays. This is particularly true of brands that function as status symbols. Messaging may be deliberately created by a company through marketing efforts but also occurs through individuals that interact with the company directly or indirectly. Customers, employees, owners, competitors, vendors, and regulators may all add to the pool of company messaging. Whether good or bad, this messaging contributes to company awareness and its overall image and reputation.

Business Interactions may occur at both the enterprise level and personal level with owners and/or employees. While interactions with some companies such as Amazon or Google may only occur at the enterprise level, in other businesses human interaction may be most prominent. Value provided to a customer through personal interactions can contribute to the enterprise goodwill of the business and/or the personal goodwill of the individual providing service. Elements of other intangibles may contribute to business interactions that lead to sales and greater customer loyalty.

Personal Experience results from business interactions. This experience may also be shaped by market messaging. For instance, messaging about certain luxury brands may contribute to the way individuals experience the brand at an emotional level. These experiences form the basis of further contributions to the pool of brand messaging by individuals as part of a market feed-back loop.

Awareness, Image and Reputation are driven by market messaging and personal experiences. While a trademark may form the initial basis of brand awareness, deeper associations with the brand and what it stands for form the basis of image and reputation.

Goodwill, Brand Equity and Celebrity

The personal goodwill of owners and employees can contribute to brand equity. Businesses are beneficiaries of these contributions while the individuals creating the goodwill remain associated with the business. But what happens when they leave?

Earlier I cited interactions with employees at Apple and Chick-fil-A. In both examples, I noted how benefits from employee contributions to my positive experiences accrued to the enterprise and how the departure of these employees would not divert my business. Contrast that to a situation where an owner sells a business then opens a competing business across the street which then attracts customers of the business that was just sold. In that situation, the buyer may have purchased certain assets of the business—even its name—but the draw of the previous owner (i.e., personal goodwill) was strong enough to divert customers. For a buyer, this is the situation that non-compete and non-solicitation agreements are intended to prevent.

So what about a very special type of business, musical acts, where one employee, the lead singer, is often considered to be the "face" and quite literally the "voice" of the business? Rock and roll history is littered with stories of lead singers leaving bands for various reasons and in many cases, the bands carried-on with replacements.

The British band Deep Purple was formed in 1968 and lived through multiple incarnations with six different lead singers. These singers contributed their personal goodwill due to work in previous bands and took their personal goodwill with them as they left to join new bands. Through it all, the Deep Purple brand remained intact. In 1980, original lead vocalist Rod Evans and a group of studio musicians launched a band using the Deep Purple name without consent. This group became known as the "Bogus Deep Purple." A lawsuit ensued which resulted in other band members reclaiming their rights to the name while precluding future use by Evans. In 1984, a reunited Deep Purple with vocalist Ian Gillan released Perfect Strangers, their first album since 1976, which ultimately charted in the top-20.15 Deep Purple's fan loyalty and resulting goodwill was largely tied to the band (i.e. the enterprise) not any specific lead singer.

Formed in the 1970s, AC/DC is one of the biggest- selling and longest-running rock bands of all time. "Highway to Hell" was released in 1979 and would become the band's first top-40 album. Months after peaking in the charts at No. 17 with "Highway to Hell," lead singer Bon Scott was found dead of acute alcohol poisoning. Five months after Scott's death, "Back in Black" was released with Brian Johnson premiering as the band's new lead singer. "Back in Black" surpassed the success of "Highway to Hell" by peaking in the charts at No. 4. In 1981 both of these past successes were eclipsed with "For Those About to Rock We Salute You" when it peaked at No. 1. In this case, the replacement contributed to greater success than the original and the enterprise goodwill of the band grew.16 Other well-known examples include Van Halen with Sammy Hagar replacing David Lee Roth and Journey with Filipino Arnel Pineda replacing Steve Perry. In these cases, the bands carried on but never recaptured prior levels of success.17

Then there's the band Chicago. Lead singer Peter Cetera was there for Chicago's first 17 albums, 12 of which peaked at top-10 positions in the charts. Following Cetera's departure to pursue a solo career, Chicago released its 18th album which peaked at 35. With the exception of a greatest hits album released after Cetera's departure, subsequent albums experienced ever-declining peaks and ultimately stopped charting.18 In this case, Peter Cetera's personal goodwill proved to be a critical element of the band's success which followed him into a solo career.

So what about superstar celebrities such as Elvis, Prince and Michael Jackson?

In the case of Prince—whose birth name was Prince Rogers Nelson—the issue of his personal brand became quite complicated from a marketing and legal perspective. Through a press release after becoming disillusioned with his record contract, Prince stated that "Warner Bros. took the name, trademarked it, and used it…The company owns the name Prince and all related music marketed under Prince." So, in 1993, Prince became "the artist formerly known as Prince" and used a self-described Love Symbol as his trademark. In 2000, the recording contract expired and Prince was able to start using his name again.19 When Prince died in April 2016, a new set of complications arose due to the fact that Prince did not have a Will and that a value needed to be placed on his estate—including a value for his post-mortem name and likeness—for tax and estate distribution purposes.

The complexities associated with the valuation of a celebrity's name and likeness may be best exemplified by Michael Jackson. Due to erratic behavior coupled with allegations of child abuse and drug abuse towards the end of his career, executors of the Jackson estate claimed his tarnished name and likeness was worth a mere $2,105 on the date of his death. In contrast, the IRS claimed his name and likeness was worth $434 million. Supporting the IRS position has been a wave of post-death business deals involving the "This Is It" documentary, Cirque du Soliel tribute shows and deals with Sony records worth hundreds of millions of dollars.20

After Elvis died in 1977, a rash of unlicensed products bearing his name and likeness flooded the market. While unauthorized merchants cashed-in on the death of Elvis, his estate was unable to pay its federal taxes. Following a series of litigation involving the unauthorized use of the Elvis name and likeness, the State of Tennessee enacted the Personal Rights Protection Act of 1984, which provided for the descendibility of personality rights, also known as right of publicity, to "executors, assigns, heirs, or devisees."21 In light of problems observed following the death of Elvis, Tennessee law made specific provisions for post-mortem rights of publicity and several other states followed suit thereafter.

Black's Law Dictionary provides the following definition:

Right of Publicity—The right to control the use of one'sown name, picture, or likeness and to prevent another from using it for commercial benefit without one's consent.

"The right of publicity is a state-law created intellectual property right whose infringement is a commercial tort of unfair competition. It is a distinct legal category, not just a 'kind of' trademark, copyright, false advertising or right of privacy," J. Thomas McCarthy, The Rights of Publicity and Privacy (2nd Edition 2000).

One distinction that exists between right of publicity and trademark lies in the fact that right of publicity deals with the commercial use of an individual's name, image and likeness—attributes of one's personal identity— whereas trademark law deals with the value of specified words and symbols which are attributes of a business identity used for commercial purposes.

However, as with Prince, a celebrity's name is often covered by a federally-registered trademark too, in which case unlicensed use may be pursued under federal trademark laws.22 But beyond that, name, image, likeness and associated rights of publicity are covered by state law. Rights of publicity further underscore how trademarks, brands and goodwill work together in the context of commercial use and economic value.

As I was concluding this paper, news of the death of fashion designer Kate Spade had just become known. When she started in 1993, with colorful utilitarian handbags, her brand and designs were tied to her personally.23 But as the business grew and other designers were added, enterprise goodwill developed.

In 1999, Spade sold a 56 percent equity interest to Neiman Marcus with the remaining 44 percent interest being sold in 2006 for a total of $93 million from both transactions. A week after concluding its purchase, Neiman Marcus sold its 100 percent interest in Kate Spade to Liz Claiborne for a reported $124 million. Liz Claiborne ultimately rebranded the entire company as Kate Spade & Co. in 2014. In May 2017, Coach purchased Kate Spade & Co. for $2.4 billion.24 At the time of its sale to Coach in 2017, Spade had not been involved with the company for over a decade.

The story of Kate Spade illustrates how goodwill can be parlayed into a powerful brand that takes on a life of its own that transcends its namesake. I'm sure Levi Strauss could relate. ■

Available at Social Science Research Network (SSRN): https://ssrn.com/abstract=3218573.

1. Fair Value is a standard of value used for purchase accounting purposes. A discussion of different standards of value is beyond the scope of this article.

2. See ASC 805-20-55-13 for GAAP in the United States and IAS 38 and IFRS 3 as related to international accounting standards. While internally-generated brands may have great value (think Coca-Cola), this value is not recognized on the company's balance sheet due to principles of conservatism in accounting which prevent intangible assets from being "marked-up." However, brand value is recognized for accounting purposes in business acquisitions where actual transactions have taken place. For instance, in 2010, Diamond Foods acquired premium potato chip maker Kettle Foods for $616 million. In its initial post-deal purchase price allocation, Diamond Foods placed a $235 million asset value on Kettle's "Brand Intangibles." In this transaction, approximately 38% of the purchase price was related to the Kettle Foods brand. (See 10-Q for Diamond Foods, Inc. filed on 12/08/2010, financial statement note #5).

3. EBITDA is an accounting-based proxy for operating cash flow and is a commonly used metric of business performance considered in mergers and acquisitions and other valuation purposes.

4. To simplify for illustration purposes, this exhibit assumes the book value of assets and liabilities noted in dark blue approximates fair value.

5. Black's Law Dictionary, Bryan A. Garner, Editor, 8th Edition, (Thomson West, 1999).

6. From a transaction accounting perspective, goodwill is calculated as the difference between the purchase price and the fair value of acquired assets, net of assumed liabilities, as of the acquisition date as illustrated in Exhibit 1. However, the purpose of this article was to explore the economic benefits of goodwill, not its technical calculation.

7. Shannon Pratt, "Overview of Enterprise and Personal Goodwill, BVR's Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill, 5th Edition, (Business Valuation Resources, 2012).

8. David Wood, "Personal Goodwill in Search of a Functional Definition," BVR's Guide to Personal v. Enterprise Goodwill, 5th Edition, (Business Valuation Resources, 2012).

9. 110 T.C. No. 18, United States Tax Court, Martin Ice Cream Company, Petitioner v. Commissioner Of Internal Revenue, Filed March 17, 1998.

10. The original version of several paragraphs in this section were published in "Is Profiting from the Online Use of Another's Property Unjust? The Use of Brand Names as Paid Search Keywords," 53 IDEA 131 (2013) (By Daniel Gervais, Glenn Perdue et al), Also selected for inclusion in the Intellectual Property L. Rev. (West 2014).

11. See Gabriela Salinas"The International Brand Valuation Manual," chap. 1 (2009).

12. See id.

13. The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires small molecule generic drugs to be chemically identical to their branded counterparts to gain approval for market entry.

14. Boonghee Yoo, Naveen Donthu, and Sungho Lee, "An Examination of Selected Marketing Mix Elements and Brand Equity," 28 J. of "The Academy Of Marketing Science" 195 (2008).

15. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/artists/deep-purple/ biography—accessed 6/4/2018.

16. https://www.billboard.com/articles/6406362/acdc-albumsranked-highest-to-lowest-charting—accessed 6/1/2018.

17. https://www.rollingstone.com/music/pictures/15-bandsthat-carried-on-with-new-singers-20130813/journey-with-arnel-pineda-2007-present-0344025—accessed 5/22/2018.

18. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chicago_discography—accessed 6/1/2018.

19. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-36107590—accessed 6/4/2018.

20. https://www.lexology.com/library/detail.aspx?g=7b17006ef851- 40b2-9911-a77adf3390cd—accessed 6/4/2018.

21. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/elvis-and-princepersonality-rights-guidance-dead-celebrities-and-lawyersand— accessed 6/4/2018 by Peter Colin Jr.

22. Additionally, certain images of individuals may also be protected by federal copyright law.

23. https://www.katespade.com/katespade-about-us/ katespade-the-history.html—accessed 6/5/2018.

24. https://www.forbes.com/sites/noahkirsch/2017/05/08/ why-kate-spade-wont-see-a-penny-of-the-2-4-billion-sale-tocoach/# 2d0d36fa5b2b, by Noah Kirsch—accessed 6/5/2018.