les Nouvelles June 2018 Article of the Month

Licensing Standards Essential Patents

Alfred Consulting LLC

Founder & General Manager

Fredericksburg, VA, USA

Introduction

A. Standards and Patents

Steve Jobs and Apple introduced the iPhone, the first smartphone, in January 2007, and a waiting world was introduced to incredible volume both in standards and in patents. Global data usage now exceeds one billion gigabytes a month and half of all mobile devices are smartphones. The growth in mobile standards from the first generation in the 1980s to the development of the fifth generation today has witnessed an amazing array of technology, one release will capture the public interest only to be replaced within a short span of time by a new technology, more useful, more ubiquitous than the last one. The key question for discussion in today's world of standards and patents is how to license the standards essential patents for the smartphone at a fair price.

Let's begin this discussion with standards. The first generation of standards included devices such as the pager, the cordless telephone and private mobile radio and systems such as the Advanced Mobile Phone System (AMPS) and the Total Access Communication System (TACS.)1 According to Tondare, Panchal and Kushnure "AMPS was introduced in 1982 providing bandwidth of 40MHz, offering 832 channels for subscribers with data rate of 10Kbps." This step forward required better batteries as did all the generations of mobile devices.

The second generation introduced new techniques, Time Division Multiple Access (TDMA), Code Division Multiple Access (CDMA) and roaming. The most widely used protocol was the Global System for Mobile Communication (GSM.) The United States used TDMA and CDMA while most of the world adopted GSM.

The third generation increased speed and capacity adding services such as streaming, mobile internet access, video calling and internet protocol television (IPTV.) The Third Generation Partnership Project (3GPP), a standards group with representation from standards organizations in the United States, Europe, China, Japan and Korea developed the International Mobile Telecommunications-2000 (IMT-2000) with data rates of 200 kbps. CDMA developed an overlay that allowed data rates over 300 kbps.

The fourth generation introduced the convergence of wired and wireless. "4G is an all IP-based integrated system will be capable to provide 100 Mbps for high mobility and one Gbps for low mobility, with end-to-end QoS (quality of service) and high security. The user services include IP telephony, ultra-broadband Internet access, gaming services and High Definition Television (HDTV) streamed multimedia."2

Work on 2G standards involved more than 886,000 person hours from 200 companies from 13 countries over 15 years. Work on 4G standards "…is ongoing and has already taken more than nine years, and more than a million person hours from participants from more than 320 companies."3

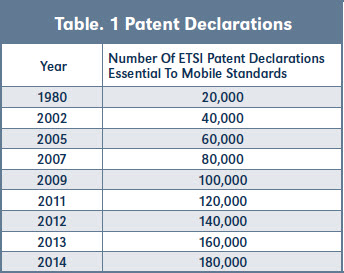

Work on patents kept pace. Baron and Pohlmann found 180,215 declarations of standards essential patents (SEPs) essential to ETSI mobile standards in September 2015. Table 1 shows the number of patent declarations as it grew year by year.4

The number of standards subject to declared SEPS is 2,134. The number subject to more than 10 declared SEPs is 1,007. The number subject to more than 100 SEPs is 308. The number subject to more than 1,000 declared SEPs is 44 and of these 43 are from ETSI. Long Term Evolution (LTE) has the largest number of declarations with 61,831 followed by Universal Mobile Telecommunication Service (UMTS) with 43,658 and Universal Terrestrial Radio Access Network UTRAN with 18,757.5

In 2014, TechIPm found that very few of the patents claimed as essential to LTE were essential to the Radio Access Network (RAN) sections of LTE. There are over 490 sections in the LTE standard. A patent essential to the LTE standard may or may not be essential to every device that implements the standard. The RAN sections of the LTE standard that are included in every mobile device are less than 70 sections. TechIPm found only 447 essential RAN patents compared to the 50,000+ claimed patents essential to the LTE standard. Assuming this proportion holds there were roughly 550 patents essential to the RAN sections of the LTE standard by September 2015.

B. Back To Case Law

A patent is a negative right to exclude others from making, using or selling one's invention and it includes the right to license others to make, use or sell it. A patent is a grant of some privilege, property or authority, made by the government or sovereign of a country to one or more individuals.6 In their book, Cases and Materials on Patent Law, Martin Adelman and his fellow authors quote White, Patent Litigation: Procedure and Tactics and U.S. statutes.

To obtain as damages the profits on sales he would have made absent the infringement, i.e., the sales made by the infringer, a patent owner must prove: (1) demand for the patented product, (2) absence of acceptable non-infringing substitutes, (3) his manufacturing and marketing capability to exploit the demand, and (4) the amount of profit he would have made.

When actual damages, e.g., lost profits, cannot be proved, the patent owner is entitled to a reasonable royalty. 35 U.S.C. § 284. A reasonable royalty is an amount "which a person, desiring to manufacture and sell a patented article, as a business proposition, would be willing to pay as a royalty and yet be able to make and sell the patented article, in the market, at a reasonable profit." Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. v. Overman Cushion Tire Co., 95 F.2d 978 at 984…7

Given the volume of smartphone sales, a patent owner of a smartphone SEP would certainly find it easy to prove (1) demand for the patented product; because it is covered by standards; (2) absence of acceptable non-infringing substitutes; (3) his manufacturing and marketing capability to exploit the demand; (4) the amount of profit he would have made. Since sales of smartphones have been brisk and Apple and Samsung are the only profitable manufacturers, perhaps unless the complaint was made by Apple or Samsung, this may be difficult to prove (4). It would be less difficult to prove (4) for a chip maker.

Many cases make use of the fifteen Georgia-Pacific Factors to determine reasonable damages.i Fong, Lai and Liu found, "Using LexisNexus [LexisNexis], we have identified cases where judges have referenced the Georgia-Pacific case since 1995. There are 96 cases cited this case (Appendix 1). After some manual sorting, we have identified those cases where these factors have been discussed (35 cases out of 96, i.e. 36 percent) and included them in our study. This set of cases was used to determine the inter-relationship between the various factors and categorise them to have a structured approach to use the Georgia-Pacific 15 factors."8

Fong et al cite a Durie and Lemley 2010 study that "…have suggested a structured approach to calculate reasonable royalties based on the 15 factors cited in Georgia-Pacific case. They suggested that most of the 15 factors essentially answered three questions:

- What is the marginal contribution of the patented invention over the prior art?

- How many other inputs were necessary to achieve that contribution, and what is their relative value? and

- Is there some concrete evidence suggesting that the market has chosen a number different than the calculus that results from (1) and (2)?"

Fong et al note in their conclusion, "…it has also been demonstrated the Georgia-Pacific factors can be quantified using the Nash bargaining solution. This can serve as a guideline for expert witnesses to base their reasonable royalty calculations on. In addition, the solution can also be used in practical licensing negotiations to guide practitioners."

C. The Smartphone Royalty Stack

Considering item number two of the Georgia-Pacific factors: "The rates paid by the licensee for the use of other patents comparable to the patent-in-suit", the "rates paid" not only vary widely, but use a different base on which to compare the patents-in-suit. The question of royalty based on the price of the device in which a standard is practiced or royalty based on the components that practice the standard is still subject to cases in court and license practice in the market.

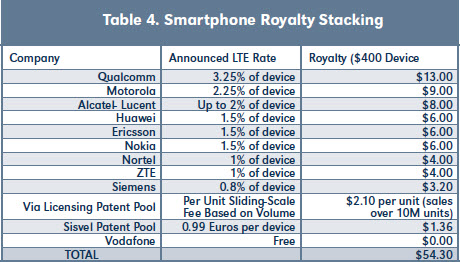

Armstrong, Mueller and Syrett argued that:

The data show that royalty stacking is not merely a theoretical concern. Indeed, setting aside off-sets such as "payments" made in the form of cross-licenses and patent exhaustion arising from licensed sales by component suppliers, we estimate potential patent royalties in excess of $120 on a hypothetical $400 smartphone—which is almost equal to the cost of device's components.9

Just using publicly announced royalty rates, Armstrong, Mueller and Syrett found:

In the table shown above, Armstrong, Mueller and Syrett identified the companies that have publicly disclosed royalty rates for their LTE portfolios. For each company, they then calculated the royalty that would be applicable to a $400 device based on the announced rate.10

Nortel filed for bankruptcy and sold their patents to the Rockstar Consortium including Apple, Microsoft, Ericsson, Sony, and BlackBerry in July 2011. Google bought Motorola in May 2012. ZTE joined the Via Licensing patent pool in October 2012. Rockstar sold the Nortel patents to RPX in December 2014. Google joined the Via Licensing patent pool in April 2015. Nokia bought Alcatel-Lucent in April 2015.

Note that there are two patent pools listed. Usually there is only one patent pool per technology so that licensees may gain the benefit of a license from many companies without stacking the royalty rates—that is without adding the rates. In the case of LTE, the patent pools add to the royalty stack. In 2007, the major LTE patent holders said they would publish their rates and that the combined rate would be a high single digit number, that is less than 10 percent. The first seven on this list are at 14 percent royalty, so the publication of rates approach never quite lived up to its billing.

I. Standards and GATT—The Global Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

- GATT and WTO—The World Trade Organization

The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is a multilateral agreement regulating international trade. According to its preamble, its purpose was the "substantial reduction of tariffs and other trade barriers and the elimination of preferences, on a reciprocal and mutually advantageous basis." It was negotiated during the United Nations Conference on Trade and Employment and was the outcome of the failure of negotiating governments to create the International Trade Organization (ITO.) GATT was signed by 23 nations in Geneva on October 30, 1947 and took effect on January 1, 1948. It lasted until the signature by 123 nations in Marrakesh on April 14, 1994 of the Uruguay Round Agreements, which established the World Trade Organization (WTO) on January 1, 1995. The original GATT text (GATT 1947) is still in effect under the WTO framework, subject to the modifications of GATT 1994.ii

- Purpose of GATT

Recognizing that their relations in the field of trade and economic endeavour should be conducted with a view to raising standards of living, ensuring full employment and a large and steadily growing volume of real income and effective demand, developing the full use of the resources of the world and expanding the production and exchange of goods…

- Article VIII—Fees and Formalities Connected with Importation and Exportation

1a. All fees and charges of whatever character (other than import and export duties and other than taxes within the purview of Article III) imposed by contracting parties on or in connection with importation or exportation shall be limited in amount to the approximate cost of services rendered and shall not represent an indirect protection to domestic products or a taxation of imports or exports for fiscal purposes.

- The provisions of this Article shall extend to fees, charges, formalities and requirements imposed by governmental authorities in connection with importation and exportation, including those relating to: (a) consular transactions, such as consular invoices and certificates; (b) quantitative restrictions; (c) licensing; (d) exchange control; (e) statistical services; (f) documents, documentation and certification; (g) analysis and inspection; and (h) quarantine, sanitation and fumigation.iii

- Financial Incentive

Patents grant exclusive rights that allow owners to benefit from the property they have created, providing a financial incentive for the creation of an investment in intellectual property, and, in case of patents, pay associated research and development costs according to Schroeder and Singer.iv However, Levine and Boldrin dispute the research and development justification.

Regardless of justification, there is no argument as to the growing value of intellectual property. In 2013, the United States Patent & Trademark Office approximated that the worth of intellectual property to the U.S. economy is more than US $5 trillion and creates employment for an estimated 18 million American people. The value of intellectual property is considered similarly high in other developed nations, such as those in the European Union.v

The question of financial incentive as it applies to the licensing rates of standards essential patents is therefore a GATT question. Are royalty rates limited to the approximate cost of services? In particular, do the services include the practice of product or service functions not covered by the claims of a patent? Do these services include research and development costs? What base do we use to value the royalty rate? Since the international standards for smartphones have been adopted and practiced by so many companies and organizations that their use is considered mandatory, what premium may a licensing entity reasonably charge? These are key questions in licensing today.

- The Case Law Surrounding Device Licensing

In Microsoft v. Motorola Inc. and Motorola Mobility v. Microsoft: This was a breach of contract case. Microsoft claimed that Motorola had an obligation to license patents to Microsoft at a reasonable and non-discriminatory ("RAND") rate, and that Motorola breached its RAND obligations through two offer letters. Microsoft sued Motorola for breach of contract in this court November 2010. The parties disagreed substantially about the meaning of RAND. Thus, to resolve the dispute, the court held a bench trial from November 13–20, 2012.

To establish a context for these findings and conclusions, the court outlined the details of Motorola's RAND obligation, the patents at issue in this case, and the nature of the dispute between Microsoft and Motorola.11

Motorola's RAND commitment arises out of its relationship with two standards-setting organizations, the Institute of Electrical Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and the International Telecommunications Union (ITU). The standards in this case involve wireless communications, commonly known as WiFi—IEEE Wireless Local Area Network (WLAN) called the 802.11 standard and video coding—ITU video coding standard called the H.264 standard. Both of these standards incorporate patented technology called standards essential patents—SEPs. Thus, in order to practice the standard, it is necessary to obtain a license to these SEPs from the patent owners.

Motorola offered to license its SEPs at what it considered the RAND rate of 2.25 percent.

- This letter is to confirm Motorola's offer to grant Microsoft a world-wide non-exclusive license under Motorola's portfolio of patents and pending applications having claims that may be or become Essential Patent Claims subject to a grant back license under 802.11 essential patents of Microsoft…for a compliant implementation of IEEE 802.11 Standards… As per Motorola's standard terms, the royalty is calculated based on the price of the end product (e.g. each Xbox 360 product) and not on component software (e.g. Windows Mobile Software).

- For an Xbox 360 the royalty range is from $3.83 for a $170 Xbox 360 to $7.43 for a $330 Xbox 360. Since Microsoft sold an average of 11 million Xbox 360s between 2008 and 2014, Motorola was asking for a royalty in the range of $274 million to $572 million just for the Xbox 360 product.

- Motorola offered to license its SEPs at what it considered the RAND rate of 2.25 percent of the price of Microsoft's Windows 7 and higher H.264 products.

The U.S. District Court used six factors in its analysis (1.) The court introduced the parties and their relationship to one another, (2.) The court provided background on standards, Standards Setting Organizations (SSOs) and the RAND commitment, (3.) The court developed a framework for assessing RAND terms, specifically a modified version of the Georgia-Pacific factors:

- The court introduced the parties and their relationship to one another;

- The court provided background on standards, Standards Setting Organizations (SSOs) and the RAND commitment;

- The court developed a framework for assessing RAND terms, specifically a modified version of theGeorgia-Pacific factors;

a. See Georgia-Pacific Corp. v. United States PlywoodCorp., 318 F. Supp. 1116 Southern District New York 1970.

b. The court determines that the parties in a hypothetical negotiation would set RAND royalty rates by looking at the importance of the SEPs to the standard and the importance of the standard and the SEPs to the products at issue.

- After establishing a framework, the court introduced the H.264 standard and Motorola's H.264 SEPs, analyzing each patent in turn and setting the portfolio's relative importance to the H.264 standard and to Microsoft's standards-using products;

- The court introduced the 802.11 standard and Motorola's 802.11 SEPs and analyzed each 802.11 patent using the same framework;

- The court used all of the foregoing information, along with comparables suggested by the parties, to determine an appropriate RAND royalty rate for Motorola's SEPs.

The US District Court decided that the royalty rate and range as follows:

- 1. The royalty rate for Motorola's H.264 SEP portfolio is 0.555 cents per unit.

- The upper bound is 16.389 cents per unit and the lower bound is 0.555 cents per unit.

- This rate and range is applicable to both Microsoft Windows and Xbox products.

Key factors cited include:

Section 540: To this end, in the course of a hypothetical negotiation with a SEP owner, the implementer must ask herself as a rational business person, "What is the most I can pay for a license to this particular SEP or portfolio of SEPs—knowing that I might have to license all SEPs in the entire standard—while still maintaining a viable business?"

The court looked at the Via Licensing 802.11 Licensing Pool and the MPEG LA H.264 Licensing Pool as examples to use in setting a royalty rate and avoiding royalty stacking.

Section 578: Microsoft uses as an additional comparable … the royalty rate that a third- party company, Marvel Semiconductor … pays for the intellectual property in its WiFi chips. The court agrees that the Marvell rate provides an indicator for 802.11 RAND under Factor 12 of a hypothetical negotiation because the experiences of Marvell, a third party, tend to establish what is customary in the business of semiconductor licensing.

Section 580: …the Marvell WiFi chip…enables the device to use the 802.11 Standard to transmit and receive information on radio frequency carriers. Otherwise stated, the WiFi chip uses the 802.11 Standard to communicate wirelessly.

Section 581: In the past Marvell has charged $3.00 to $4.00 per chip for WiFi chips of the kind its sells to Microsoft. 6. Section 582: Marvell pays a royalty and licensing fees to ARM Holdings … ARM provides Marvell with patent licenses and "design and know-how" Marvell needs to make its 802.11 compliant chips … Marvell pays ARM one percent of the purchase price of the chip (3-4 cents per chip.)

Section 585: Marvell considers the ARM rate an appropriate benchmark because the rate is based on the selling price of the chip, not the sale price of the end-user product into which the chip is embedded. Example testimony: A one percent royalty on a chip placed in an $80,000 Audi A8 would be $800, or about 267 times the retail price of the chip.

Another case citing the smallest saleable unit is Cornell University v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 609 F. Supp. 2d 279, 283 (2009.)vi

II. The Way Forward

- Based on the cases cited above, I disagree with the concept of whole portfolio—whole device licensing. Recent case law does not support whole device licensing and the definition of damages in patent law never supported whole portfolio licensing. In patent law, a patent owner may not charge royalty for claims that he or she does not own. Even though the license contract may state that the royalty is only for claims that the infringer is actually practicing, the alleged infringing party is doing themselves a disservice if they pay any amount of royalty for an alleged claim that is not proved. Similarly, as shown in section 585 of the Microsoft-Motorola case, chips may be placed in many devices, not just smartphones that cost $600. Some large screen TVs cost $9,000. Some automobiles cost $80,000. Boeing lists the price of its 737 as between $51.5 million and $87 million depending on the model. Once again, the alleged infringing party is doing themselves a disservice if they pay any amount of royalty for damages based on using the device price when the entire device does not infringe the alleged claim.

There is a case to be made that the component adds value to the whole device, but this case must be made in proportion to the device in question – Does an airline buy a 737 or does a customer buy a seat on a 737 entirely due to Wi-Fi on the flight?

- The IEEE has provided a guide, "Understanding Patent Issues During IEEE Standards Development." Section 44 of this guide reads as follows:

- In discussing Reasonable Rates, what is an example of a "smallest saleable Compliant Implementation that practices the Essential Patent Claim?"

- Determining the smallest saleable Compliant Implementation that practices the Essential Patent Claim is a function both of the claims in the patent and of the product or products that implement a standard. For example, assume a component is a Compliant Implementation of IEEE 802.11™ and practices the Essential Patent Claim. That component is then used in an entertainment system that is then installed into an airplane. In this example, the component is the smallest saleable Compliant Implementation of IEEE 802.11.

C. Conclusion

No one denies that a patent owner should be able to charge whatever royalty they negotiate for a patent unrelated to a standard. The key question is whether a patent owner of a standards essential patent should be able to charge a premium when much of the value of the patent is derived from the international standards organization adopting the patented technology.

In the absence of industry coming together in a patent pool with the major players assembled to avoid royalty stacking and seek a reasonable royalty based on the component practicing the standard, the courts have done the heavy lifting. The results are not all that patent owners may desire, but the results do provide patent owners with reasonable royalty based on patent law. This royalty may not pay for all research and development, but it does provide, considering the volume of smartphones in the market and yet to enter the market, a considerable sum for those patent owners willing to do the serious work of proving their patent claims.

It is time for industry to reclaim the lead from the courts. Industry, not the courts should determine reasonable royalty for cellular standards essential patents by coming together in a single patent pool and developing a royalty that will stand the test of a court challenge. ■

References

- Georgia-Pacific Corp. v. United States Plywood Corp., 318 F. Supp. 1116, 1119-20 (S.D.N.Y. 1970), modified and aff'd, 446 F.2d 295 (2d Cir.);

- The royalties received by the patent owner for the licensing of the patent-in-suit, proving or tending to prove an established royalty;

- The rates paid by the licensee for the use of other patents comparable to the patent-in-suit;

- The nature and scope of the license, as exclusive or non-exclusive, or as restricted or non-restricted in terms of territory or with respect to whom the manufactured product may be sold;

- The licensor's established policy and marketing program to maintain its patent monopoly by not licens- ing others to use the invention or by granting licenses under special conditions designed to preserve that monopoly;

- The commercial relationship between the licensor and the licensee, such as whether they are competitors in the same territory in the same line of business, or whether they are inventor and promoter;

- The effect of selling the patented specialty in promoting sales of other products of the licensee; the existing value of the invention to the licensor as a generator of sales of its non-patented items; and the extent of such derivative or convoyed sales;

- The duration of the patent and the term of the license;

- The established profitability of the product made under the patent; its commercial success; and its current popularity;

- The utility and advantages of the patent property over the old modes or devices, if any, that had been used for working out similar results;

- The nature of the patented invention; the character of the commercial embodiment of it as owned and produced by the licensor; and the benefits to those who have used the invention;

- The extent to which the infringer has made use of the invention, and any evidence probative of the value of that use;

- The portion of the profit or of the selling price that may be customary in the particular business or in comparable businesses to allow for the use of the invention or analogous inventions;

- The portion of the realizable profit that should be credited to the invention as distinguished from non-patented elements, the manufacturing process, business risks, or significant features or improvements added by the infringer;

- The opinion testimony of qualified experts; and

- The amount that a licensor (such as the patent owner) and a licensee (such as the infringer) would have agreed upon (at the time the infringement began) if both had been reasonably and voluntarily trying to reach an agreement; that is, the amount that a prudent licensee—who desired, as a business proposition, to obtain a license to manufacture and sell a particular article embodying the patented invention—would have been willing to pay as a royalty and yet be able to make a reasonable profit, and which amount would have been acceptable by a prudent patent owner who was willing to grant a license.

- WTO Legal Texts, General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, (1994).

- General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, Geneva, (July 1986).

- Doris Schroeder and Peter Singer, "Prudential Reasons for IPR Reform," University of Melbourne, (2009).

- Thomas Bollyky, "Why Chemotherapy That Costs $70,000 in the U.S. Costs $2,500 in India," The Atlantic, (2013).

- Berkley Technology Law Journal, volume 29, issue 4, annual review, (2014) 657.

- Tondare, S.D. Panchal and D.T. Kushnure, "Evolutionary Steps From 1G to 4.5G, S.M.," International Journal of Advanced Research in Computer and Communication Engineering, Vol. 3, Issue 4, (April 2014).

- Ibid.

- Boston Consulting Group, "The Mobile Revolution, Jan 2015," quoted in les Nouvelles, An Experienced-Based Look At The Licensing Practices That Drive The Cellular Communications Industry, Blecker, Sanchez & Stasik (Dec 2016).

- Justin Baron and Tim Pohlmann, Mapping Standards to Patents using Databases of Standards-Essential and Systems of Technological Classification, (September 2015).

- Ibid.

- Black's Law Dictionary, sixth edition, (1990) 1,125.

- Martin J. Adelman, Randall R. Rader, John R. Thomas and Harold C. Wagner, Cases and Materials on Patent Law, second edition, (2003) 943-944.

- Hoi Yan Anna Fong, Yuan Ching Lai, Shang Jyh Liu, Quantified the Georgia-Pacific Factors for Calculating Reasonable Rates, Review of Integrative Business & Economics Research, vol. 2 (2), (2013) 261-275.

- Ann Armstrong, Joseph J. Mueller, Timothy D. Syrett, Wilmer Hale, The Smartphone Royalty Stack: Surveying Royalty Demands for the Components Within Modern Smartphones, (2014) 2.

- Ibid., (13-14).

- Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Case No. C10- 1823JLR, April 25, 2013, 207 pages, United States District Court Western District of Washington at Seattle, James L. Robart, presiding judge.