Survey Results Confirm Growing Trend In Favor Of ADR

World Intellectual Property Organization, Arbitration and Mediation Center

Legal Officer

Geneva 20, Switzerland

Kirkland & Ellis LLP

Partner

Chicago, IL, USA

For companies, research entities, universities and others, intellectual property (IP) has become an essential business asset as well as a means of creating value. It is being developed and exploited on an increasingly international level in various contractual relationships, such as research and development contracts, consortium agreements, licenses, purchase contracts, distributorships and joint ventures. With the increase of such transactions, the number of IP disputes increases. Disputes arising in relation to IP assets as critical elements of economic value can cause serious damage. The resources required to handle such disputes can be considerable, especially if the dispute involves litigation in multiple countries. At the same time, such disputes place a serious burden on the continuation and expansion of business. Careful consideration of the risks associated with technology-related disputes goes a long way in preventing, and resolving disputes. A strategy to manage such risks and to resolve any potential disputes rapidly and cost-effectively, therefore, is critically important.

To gain a better understanding of technology-related dispute resolution strategies and practices, the WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center (WIPO Center) recently conducted the international WIPO International Survey on Dispute Resolution in Technology Transactions1 (Survey) to obtain statistical information on the current use of alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms, such as mediation and arbitration, as compared to court litigation when it comes to resolving such disputes.

WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center

The WIPO Center2 promotes, on a not-for-profit basis, the resolution of international commercial disputes between private parties through Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) mechanisms, including arbitration, mediation and expert determination. It administers proceedings under the WIPO Mediation Rules, the WIPO Arbitration Rules, the WIPO Expedited Arbitration Rules and the WIPO Expert Determination Rules.3 While these WIPO Rules are appropriate for all commercial disputes, they contain provisions on confidentiality and technical and experimental evidence that are of special interest to parties to IP disputes. To date, the WIPO Center has administered over 350 cases, with a 27 percent increase of its caseload in the past 3 years.

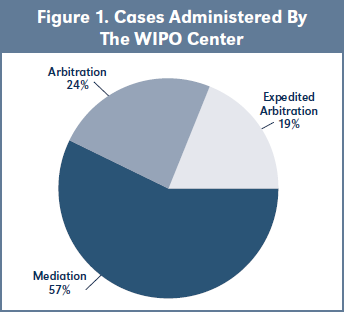

The following diagram shows the split in the cases administered by the WIPO Center among the different procedures:

Source: WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center

The subject matter of the mediation and arbitration cases so far administered by the WIPO Center includes patent, know how and software licenses, franchising agreements, trademark coexistence agreements, distribution contracts, joint venture agreements, research and development contracts, technology transfer agreements, technology-sensitive employment contracts, mergers and acquisitions with important intellectual property aspects, sports marketing agreements, and publishing, music and film contracts, as well as cases arising out of agreements in settlement of prior court litigation.

Parties in cases administered by the WIPO Center so far are based in Asia, Europe and North America. Of those parties, 32 percent are involved in the IT sector, 14 percent in pharmaceuticals, biotechnology and life sciences, 16 percent in mechanical, 10 percent in entertainment, 4 percent in luxury goods and 1 percent in chemicals. The remaining 23 percent are involved in a range of other areas. The amounts in dispute range between EUR 15,000 Euros and USD 1 billion.

Seventy-six percent of mediation and arbitration cases administered by the WIPO Center are based on dispute resolution clauses4 included in existing agreements between the parties stipulating that future disputes shall be submitted to WIPO mediation and/or (expedited) arbitration. The remaining 24 percent of mediations and arbitrations are based on agreements specifically submitting an existing dispute to WIPO mediation or (expedited) arbitration. Such disputes relate, for example, to patent infringement.

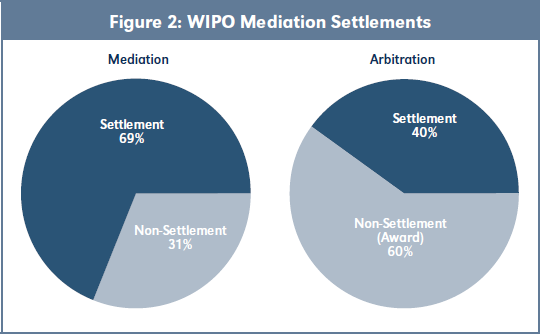

Sixty-nine percent of WIPO mediations settle, as

do 40 percent of WIPO (expedited) arbitration cases. See Figure 2.

Source: WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center

The increasing awareness and use of WIPO ADR is reflected by the incorporation of the WIPO Center's clauses in model agreements, such as the DESCA (Development of a Simplified Consortium Agreement for the Seventh Framework Programme (FP7)) model consortium agreement, which has been developed for multi-party collaborations in the area of research and development and which recommends WIPO Mediation Followed, in the Absence of a Settlement, by WIPO Expedited Arbitration.5 Also, the Intellectual Property Agreement Guide (IPAG),6 which provides model agreements for non-disclosure agreements, research contracts, research and development framework contracts, material transfer agreements, patent licenses and intellectual property purchase agreements, includes WIPO Expedited Arbitration as stand-alone ADR dispute resolution mechanism, and WIPO Mediation followed, in the absence of a settlement, by WIPO Expedited Arbitration. Further, the use of WIPO ADR has been publicly recognized, for example, in the modified Final Order of the Federal Trade Commission involving Motorola Mobility LLC and Google Inc., issued on July 23, 2013, which mentions arbitration, including WIPO arbitration, in relation to a dispute on licensing Google's standard-essential patents on fair, reasonable, and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms.7

Comments by Russell E. Levine

Based on my experience and on experiences that others have shared with me, I believe that administered ADR mechanisms are far better than non-administered procedures. The WIPO Center in particular has several advantages over other arbitral institutions, including locations in Geneva and Singapore and its status as an international agency. Since the WIPO Center is a not-for-profit organization, its cost structure is very competitive, and in my experience, lower than other arbitral institutions. The WIPO ECAF system, which allows parties and others involved in a case to submit communications electronically into a secured online docket, helps make the overall process extremely efficient. The WIPO database has over 1,500 IP arbitrators/mediators with expertise in all areas of technology, and from over 70 jurisdictions. Another advantage, in my view, of the WIPO Center is its long history and experience. It was established in 1994 to promote the resolution of IP and related disputes and over the years has developed and refined a comprehensive set of rules and procedures, including rules for expedited arbitration.

About the Survey

The Survey was distributed to companies, research organizations, universities, government bodies, law firms, individuals and other entities involved in technology transfer and technology disputes worldwide. Its findings are based on the 393 responses received by the WIPO Center from small (employing 1-10 people) to large entities (employing over 10,000 people) in 62 countries and operating in many different business areas, including pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, information technology, electronics, telecommunications, life sciences, chemicals, consumer goods and mechanical engineering. In addition to written submissions, over 60 interviews were conducted by telephone with stakeholders in 28 countries.

Participants provided information about the types of technology-related agreements which they concluded in the past two years, the types of disputes arising from these agreements, the methods used to resolve them and the reasons behind this.

"The survey confirms that parties to technologyrelated agreements are worried about the high costs and lengthy timelines of disputes, especially in an international context," noted WIPO Director General Francis Gurry at the launch of the survey report. "While court litigation remains the default path, survey responses indicate that ADR offers attractive options in terms of cost and time, as well as enforceability, quality of outcome, and confidentiality," he added.

Comments by Russell E. Levine

The WIPO Survey results are consistent with what I have seen in my practice and what I have heard at LES local chapter meetings, LES (USA & Canada) annual and mid-year meetings, and LESI meetings. There is significant and growing interest in exploring alternatives to litigation. Companies large and small, public and private, and domestic and foreign are all considering alternatives to litigation to resolve disputes, and are putting ADR clauses into license agreements, joint development agreements, and other agreement involving and relating to IP. Almost every settlement agreement and license agreement that I have been involved in this year has included an ADR clause. If the parties are both U.S. parties, the preference is for mediation and/or arbitration utilizing a U.S.-based administrator, such as JAMS or CPR. In one agreement, in the electronics industry, the parties also specified the city in which the mediation was to occur so as to reduce travel costs for both sides.

I have seen an even greater interest in ADR clauses when the parties to the agreement being negotiated are based in different countries. In a recent license deal in the automotive industry, the licensor was based in Europe and the Licensee was based in the U.S. Understandably, neither wanted a dispute to be resolved via litigation in the home country of the other, so they selected arbitration in a neutral location.

The type of entity has an impact on the willingness to use an ADR mechanism. For example, universities, research institutes, and smaller companies tend to favor mediation and arbitration. These entities in particular are sensitive to costs, and simply may not have the resources necessary to withstand lengthy litigation.

Agreements and Occurrence of Disputes

Of the types of agreements listed in the Survey, participants mostly frequently concluded non disclosure agreements (NDAs), followed by assignments, licenses, agreements on settlement of litigation, research and development (R&D) agreements and merger and acquisition (M&A) agreements. Reflecting the globalized business landscape, over 90 percent of participants indicated they had concluded agreements with parties from other jurisdictions, and 80 percent had concluded agreements relating to patents granted in several countries. The choice of applicable law made in these agreements was influenced especially by the location of the participants' headquarters and the primary place of their operations.

The Survey showed that while, overall, disputes occurred in relation to some 2 percent of participants' technology-related agreements, licenses most frequently gave rise to disputes (among 25 percent of participants). R&D agreements ranked second (among 18 percent participants), followed by NDAs (16 percent), settlement agreements (15 percent), assignments (13 percent), and M&A agreements (13 percent). Licensing disputes concerned issues such as the scope and existence of a license, quality standards, profits and determination and payment of royalty rates.

WIPO Center Experience: This reflects the experience of the WIPO Center with 42 percent of the technology-related cases handled by the WIPO Center relating to licenses, 7 percent to R&D agreements and 2 percent to settlement agreements.

Comments by Russell E. Levine

ADR can be particularly useful to expeditiously resolve disputes involving so-called Most Favored Nations (MFN) provisions. Such disputes often arise when the licensee believes that the licensor has granted a license to a third party with a more favorable royalty rate or more favorable terms and conditions, and the licensee believes that, pursuant to the MFN clause in its agreement, it is entitled to the benefit of this allegedly lower rate and/or more favorable terms. ADR also can be useful to expeditiously resolve disputes regarding whether second and subsequent generation products are "Licensed Products" and thus subject to the royalty provisions in the agreement. I have also seen ADR used to quickly resolve disputes relating to assignment clauses and disputes relating to audit rights.

Choice of Dispute Resolution Clauses

While there is a general perception that negotiations of dispute resolution often play a very limited role, 94 percent of respondents confirmed that they negotiate dispute resolution clauses as part of their contract negotiations. The most commonly negotiated stand-alone dispute resolution clause provides for court litigation (32 percent), followed by (expedited) arbitration (30 percent) and mediation (12 percent). Mediation is also included where parties use multitier clauses (17 percent of all clauses) providing for mediation prior to court litigation, (expedited) arbitration or expert determination. Where ADR is used, the choice of arbitral institution broadly corresponds to the location of respondents' headquarters.

WIPO Center Experience: Sixty-six percent of WIPO cases have been based on stand-alone dispute resolution clauses out of which 38 percent provided for arbitration, 25 percent for expedited arbitration and 38 percent for mediation. In 34 percent of cases parties included multi-tier dispute resolution clauses providing for mediation, followed by (expedited) arbitration.

Comments by Russell E. Levine

One advantage of contractual-based ADR is that the parties can structure the ADR process to best suit their dispute resolution needs. For example, the parties can limit the issues, limit the amount and type of discovery, and limit the length of the hearing. The parties also can specify certain characteristics an arbitrator should have such as a B.S. (Bachelor of Science) in Electrical Engineering or a familiarity with U.S. Patent law. I have seen clauses that require the arbitrator to issue a written decision within 60 days of submission of the last post-hearing brief and numerous other clauses all agreed to by the parties at the time the agreement was entered into, and all having the effect of expediting and reducing the cost of dispute resolution.

When asked about trends, respondents generally confirmed a trend towards out-of-court dispute resolution mechanisms.

Comments by Russell E. Levine

I have often been asked by clients and others about trends in the use of ADR and, prior to the WIPO Survey, obtaining broad-based information and statistics on such trends had proven difficult. The Survey has some of the most comprehensive data that I have seen and it sheds light on the current trends in a wide range of industries and from across the globe.

In the U.S., one reason for the growth in the use of ADR are Court Orders requiring the parties to participate in an ADR mechanism. The Alternative Dispute Resolution Act of 1998 requires federal district courts to authorize, by local rule, the use of at least one ADR process in all civil actions. As a result, most district courts have adopted such rules and increasingly are requiring or encouraging parties to engage in ADR or at least to have discussions about ADR.

For example, the Northern District of Georgia's Local Civil Rules (as well as the local civil rules of many other district courts) include an ADR provision "for the resolution of civil disputes with resultant savings in time and costs to litigants and to the court, but without sacrificing the quality of justice or the right of the litigants to a full trial in the event of an impasse following ADR." The district judge "may in his or her discretion refer any civil case to a non-binding ADR process," or, with the parties' consent, "may refer any civil case to binding arbitration, binding summary jury trial or bench trial, or other binding ADR process." The timing of such referrals is left to the discretion of the district judge. The rules contain extensive provisions requiring the parties' to consider ADR at the Early Planning Conference, the selection of an ADR neutral, the submission of required documents and memoranda, the procedures to be followed at the conference (including attendance by both lead counsel and the clients), reporting back to the district judge, and ADR fees. The Northern District of Illinois requires, in the form Report of the Parties' Planning Meeting incorporated into the district's Local Patent Rules, the identification of "any alternative dispute resolution procedure that may enhance settlement prospects." The International Trade Commission's rules permit Administrative Law Judges hearing Section 337 patent infringement investigations to direct the parties to discuss settlement.

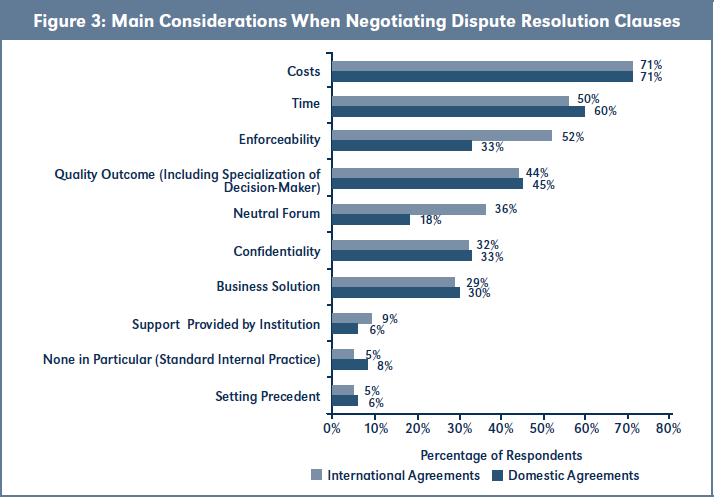

Source: WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center, International Survey on Dispute Resolution in Technology Transactions

Prime Considerations for Dispute Resolution Mechanisms

Cost and time are the prime concerns when negotiating dispute resolution clauses, both in domestic and international agreements. The Survey shows that for international agreements, other considerations include enforceability and forum neutrality. Finding a business solution, however, is the prime objective of those focusing their dispute resolution strategy on mediation, both for international and domestic agreements. See Figure 3.

Objectives in Patent Disputes

While the main objectives of claimant parties in patent disputes were to obtain damages/royalties (78 percent), a declaration of patent infringement (74 percent), and/or injunctions (53 percent), respondent aimed at declaration of patent invalidity (73 percent), a negative declaratory judgment (33 percent), and/ or a declaration of patent infringement (33 percent).

Comments by Russell E. Levine

The need for an ADR mechanism in patentrelated disputes, and for an ADR clause in patent-related agreements, is in my view greater than when dealing with other types of IP rights. The complexity of patent-related disputes often results in lengthier and more costly litigation as compared to copyright or trademark litigation, for example. As the Survey results show, costs and time are the two main considerations when negotiating dispute resolution clauses and a properly structured ADR mechanism can reduce the time and cost needed to resolve a dispute. For example, I recently represented a party in the automotive industry in litigation with its primary competitor. The settlement agreement included an escalating dispute resolution mechanism that started with discussions between executives and concluded if necessary with a binding arbitration. In their effort to control costs and to speed up the entire process, the parties agreed that any future patent dispute had to be initiated within a set time period triggered by the issuance of the patent or introduction of the accused product. The parties also limited the issues to infringement and validity, and prevented issues of willfulness or inequitable conduct from being raised in the proceeding.

WIPO Center Experience: Some 40 percent of the WIPO Center's arbitration and mediation cases relate to patents. In these cases—almost all of which are contractual—requested remedies include damages, royalty payments, declarations of non-performance of contractual obligations and/or of patent infringement, a declaration of unenforceability of a patent against a licensee, or principally in mediation, entering into a contract.

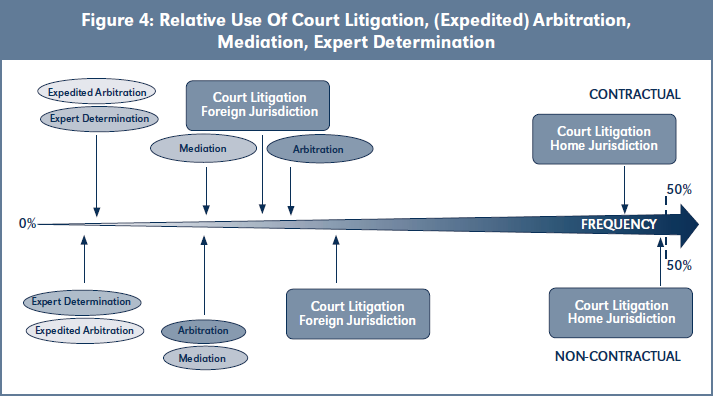

Source: WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center, International Survey on Dispute Resolution in Technology Transactions

Source: WIPO Arbitration and Mediation Center, International Survey on Dispute Resolution in Technology Transactions

How Disputes Were Resolved

Broadly consistent with the Survey findings concerning the choice of dispute resolution clauses, the most common mechanism used to resolve technology disputes was court litigation in both home and foreign jurisdictions followed by arbitration, mediation, expedited arbitration and expert determination. See Figure 4.

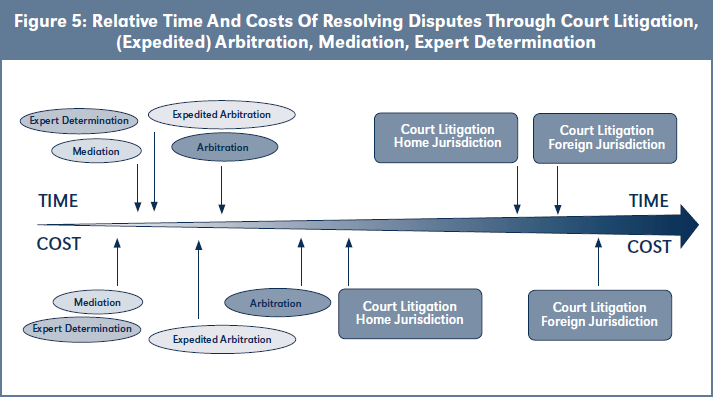

Time and Costs

The respondents spent more time and incurred significantly higher costs in court litigation than in arbitration and mediation. The estimated duration of court litigation in a home jurisdiction was on average 3 years and costs around U.S. $475,000. Litigation in another jurisdiction takes around 3.5 years with legal fees of just over U.S. $850,000.

In contrast, the Survey shows that mediation takes on average 8 months, and in the majority of cases costs less than U.S. $100,000. Arbitration takes on average just over a year and typically costs around U.S. $400,000. See Figure 5.

WIPO Center Experience: By comparison, in the WIPO Center's experience, mediation under WIPO Rules takes on average 5 months and costs on average U.S. $21,000. Arbitration cases under the WIPO Expedited Arbitration Rules on average take 7 months and cost around U.S. $48,000 and cases under the WIPO Arbitration Rules, often involving patents protected in several jurisdictions, on average take 23 months and cost some U.S. $165,000 (48 percent of such cases involving a three member tribunal and 52 percent a sole arbitrator).

On top of the monetary costs, dispute resolution also ties up the time of business executives and others participating in the proceedings. Involvement in such disputes can also translate into reduced productivity and missed business opportunities.

Comments By Russell E. Levine

I agree with the WIPO Survey results. Mediation is faster and less expensive than arbitration and both are faster and less expensive than litigation. In a recent arbitration in which I represented the respondent, the arbitration hearing was held seven months after the complaint was filed and the arbitrators decision issued one month later. I have found that the recipe for success in arbitrations is not that different from how we prepare for jury trials in the U.S. Indeed, good arbitration practice is not much different from good trial practice, although more emotional jury persuasion techniques are generally less effective and can even be counterproductive before a panel of experienced judges or patent litigators serving as arbitrators.

For mediation in the U.S. and with U.S.-based companies, a few tried-and-true practices generally make the process more likely to end successfully:

- Bring a decision maker from the client and include him or her in the preparations. Many mediators, especially magistrate judges, expressly require this. You should feel free to allow the decision maker to meet directly with his or her counterpart or with the mediator. If you have undertaken all necessary preparations, there is nothing to fear and much potentially to be gained. In a case I mediated years ago in the District of Delaware, involving back-end, financial transaction technology, the other side did not send the decision maker. The person they sent "agreed" to a proposed deal, the Magistrate Judge, who was the mediator, told the District Court Judge that the case had been settled and the parties went back home while the lawyers stayed to draft the final settlement agreement. The following day, the Magistrate Judge received a call from the person the other side had sent and was told that the proposed deal had been rejected by senior management, as had the entire deal structure. Instead of a running royalty structure, the other side now wanted a lump sum structure. Needless to say, the dynamics of the mediation dramatically changed.

- Focus on what you need, not what you want. Mediation is not the time to "win." There is nothing wrong with tough negotiating, but set a goal that you can live with and aim for it.

- Leave emotions at the door. Where the parties have a personal or professional animosity toward each other, this can be difficult. In those cases, sometimes a bit of "venting" can be therapeutic and beneficial if properly managed by an experienced mediator who can keep things in hand. Ultimately, though, mediation is a business negotiation and should be treated as such. Labeling the other side, even internally, as a "patent troll," "thief," or "heartless corporation" is never productive.

- Think carefully about opening statements. It is usually a waste of time to use an opening statement to try to "convince" the other side or a mediator, especially one using a facilitative approach, of the rightness of your case. Where an opening statement can be helpful, however, is in demonstrating to the opposing client that you are prepared to litigate, know your case, and can advocate persuasively. But, in most cases, the parties know that the other side is prepared and has quality lawyers and thus, opening statements tend to create emotions and can be counter-productive to the process. Unless there is a very good reason to have opening statements, I believe that the best practice is to dispense with them.

- Avoid scheduling multiple sessions in advance. Schedule one and go into it with as much optimism as possible. Negotiations tend to work better if there is a deadline and a sense of "crunch time." Moreover, if multiple sessions are scheduled, say months apart, the early sessions tend to become "smoking out" sessions and parties tend to hold back to see if they can push for more from the other side. Certainly if progress is being made, the parties should schedule another session, but that is something that should be done at the end of the day, not prior to the start of the mediation.

- Select a mediator who is willing to get, and stay, involved. Many mediators take great pride in their settlement rates and will do whatever it takes to get the case resolved.

- Memorialize any agreement in a written term sheet. This should include not only payment terms, but license scope, confidentiality, and other such provisions, to avoid a deal later blowing up over what the parties assumed they could later work out. Of course, if it is feasible to prepare the definitive settlement agreement while all parties are present, it is preferable to do so.

Some Observations

It is clear that no one dispute resolution mechanism can offer a comprehensive solution in all circumstances. Indeed, each transaction is likely to have its own dispute resolution requirements. It is for the parties involved to assess the specific circumstances of a transaction and to determine the most appropriate way to resolve any disputes that may arise. The Survey, however, does offer some useful guidance for those involved in developing dispute resolution strategies.

Key insights include:

- The need to anticipate the risk of disputes in contracts. Although dispute resolution provisions are often regarded as a relatively minor element in contract negotiations, the time and costs associated with any subsequent dispute means that parties cannot afford to ignore this aspect.

- The need to take account of the risk of foreign litigation and anticipate the international nature of the parties, rights and law involved.

- The cost of court litigation in a foreign jurisdiction, and sometimes in a home jurisdiction, typically exceeds that of ADR mechanisms. When crafting dispute resolution strategies, it is therefore important while taking account of the specifics of a given transaction, to focus on keeping costs and time to a minimum.

- Mediation can be a valuable part of a dispute resolution policy, with high settlement rates yielding significant time and cost savings. Adding arbitration as a next step in a multi-tier approach can enhance the chances of settlement if mediation fails.

- In relation to international patent disputes, which have important time and cost implications, when deciding whether to opt for court litigation or ADR mechanisms, it is important to take account of any existing specialized courts and judges, bifurcation of proceedings, availability of injunctions, possible parallel litigation, and enforceability.

Comments by Russell E. Levine

The WIPO Survey shows that ADR has become more common in resolving patent infringement, patent license and other technology-related disputes. This trend will continue as more and more agreements contain ADR clauses. In my opinion we also will continue to see parties agree to move existing litigation matter out of court and into an ADR process. In this regard, there is always a tension in determining the most effective time to move the case from court to ADR or to stay the litigation while utilizing an ADR mechanism. When ADR is done early, the cost savings are greatest and the parties are generally less entrenched in their positions and have had less opportunity for the case to have become "personal." On the other hand, however, the parties will have had less opportunity to gather necessary information to evaluate their position. While this is less of an issue in binding arbitration, in which the arbitration process itself may allow for discovery, depending in particular on the law of place of arbitration and the parties' agreement), when mediation or expert determinations are used, a process that occurs too early may be less fruitful. In my experience, if the parties are using mediation or expert determinations, an ideal time is usually following the exchange of infringement, invalidity, and (if applicable) non-infringement contentions, along with the accompanying document productions, but before any depositions or significant document production. This generally allows the parties to gain enough information about the merits of the case without incurring the most significant discovery expenses or the cost of claim construction briefing and a claim construction hearing. Some limited amount of damages discovery (often in the form of an exchange of summary charts) also is helpful. If the case is likely to turn on a claim construction argument, the parties may want to consider a non-binding claim construction on one or two key terms by the arbitrator or mediator.

The type of ADR most likely to be successful will vary depending on the nature of the dispute and the dynamics of the parties. It is important to think these issues through. If the parties seem to recognize that there are merits to both sides of the case, or if the parties have an ongoing business relationship, mediation may be the best choice. If the parties are both highly certain that they will win at trial and antagonistic toward any negotiation, arbitration might be a better option. Even within the options of mediation, expert determinations, or arbitration, a number of additional options, and even different styles of neutrals and procedures, are available and should be considered. Whatever process is selected, it is important to document the decision between the parties, addressing such issues as whether the process will be binding, how a neutral will be chosen, confidentiality, appeal rights, the issues that will be addressed, etc. And, rather than re-inventing the wheel, the parties likely would be far better off designating an arbitral institution, such as WIPO's Arbitration and Mediation Center, and using its rules and procedures.

- The results of the WIPO International Survey on Dispute Resolution in Technology Transactions are available at: www.wipo.int/amc/en/center/survey/results.html. The Survey was developed with the support of an expert group comprising in-house counsel and external experts in technology disputes from a broad range of jurisdictions and business areas, various professional associations, including the International Association for the Protection of Intellectual Property (AIPPI), the Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM), the Fédération Internationale des Conseils en Propriété Industrielle (FICPI) and the Licensing Executives Society International (LESI), and with the assistance from the WIPO Economics and Statistics Division.

- Information on WIPO Center is available at: http://www.wipo.int/amc/en. For details on the history of the creation of the WIPO Center, see: Development of WIPO's Dispute Resolution Services, World Intellectual Property Organization, 1992-2007, Part III, pp. 93-104, www.wipo.int/amc/en/history/.

- A general description of the procedures administered by the WIPO Center can be found in an article published by the WIPO Center in Volume XLII No. 1 (March 2007) of les Nouvelles (http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/amc/en/docs/nouvellesmarch2007.pdf).

- Recommended WIPO Contract Clauses and Submission Agreements: http://www.wipo.int/amc/en/clauses/index.html.

- DESCA model agreement: http://www.desca-fp7.eu/.

- IPAG model agreements: www.ipag.at.

- Modified Final Order of the Federal Trade Commission issued July 23, 2013: http://www.ftc.gov/os/caselist/1210120/130724googlemotorolado.pdf.